Why Freemasonry Claims the Liberal Arts

The Liberal Arts explicitly enter Masonic rituals during the nineteenth century, at the moment when the Fellowcraft’s path takes shape as a genuine passage from gesture to knowledge. The liberal arts in Freemasonry are not, however, a simple scholastic reprise of an old educational programme. Their presence continues to cause unease, to the point that some rituals now prefer the more contemporary language of the sciences. But what does this replacement mean, and what are we seeking to avoid by erasing this older map of knowledge? For the liberal arts in Freemasonry raise a more radical question than it may seem: what is a form of knowledge that liberates, and from what does it truly liberate?

- 1. Liberal arts and servile arts: a foundational divide

- 2. The Old Charges: bringing the craft into the realm of knowledge

- 3. From the Fellowcraft to the Liberal Arts: moving from gesture to discernment

- 4. From Geometry to the Royal Art: an assumed claim

- 5. Conclusion – Liberal Arts and the Royal Art

- 6. FAQ – Liberal Arts and the Royal Art in Freemasonry

- 7. Podcast – Liberal Arts and the Royal Art

Liberal arts and servile arts: a foundational divide

To understand what the liberal arts in Freemasonry truly signify, one must accept passing through a certain unease. An unease that is historical, but above all symbolic. The Liberal Arts, as they take shape in Late Antiquity and then throughout the Middle Ages, are not neutral. They establish a hierarchy. On one side, a form of knowledge considered free and noble, oriented toward the formation of the mind; on the other, the so-called servile or mechanical arts, linked to manual work, utility, and production. This opposition is not merely a pedagogical classification. It commits a particular conception of the human being.

The Liberal Arts are not called such because they would be more pleasant or higher by nature, but because they are supposed to free those who study them from immediate necessity. They form a human being capable of thinking, speaking, measuring, and contemplating. By contrast, the mechanical arts confine the individual within the constraint of doing. The carpenter, the stonecutter, the blacksmith produce, transform, build — yet, according to this view, without access to the form of knowledge that orders and justifies their gesture.

This divide is a harsh one. All the more so because the building trades occupy a central place in medieval society. Cathedrals, abbeys, palaces, bridges: Europe is quite literally built by the hands of those who nonetheless continue to be regarded as intellectually inferior. The Church itself, while depending on these trades, does not hesitate to recall that the mechanical arts are also those that produce weapons, thereby reinforcing their moral disqualification.

It is here that the question becomes Masonic. What does Freemasonry, arising precisely from these trades, do when it lays claim to the Liberal Arts? It does not merely adopt a prestigious vocabulary. It takes a position within an ancient conflict. The liberal arts in Freemasonry are not an erudite ornament, but an implicit response to a centuries-old marginalisation.

For what medieval builders already intuited — and what Freemasonry would later articulate — is that gesture is never pure mechanism. To build presupposes an understanding of space, number, proportion, and rhythm. In other words: Geometry, Music, Arithmetic. What medieval classification artificially separated, the building site already brought together.

By claiming the Liberal Arts, Masonry does not deny the craft. It refuses to allow it to be reduced to a merely servile function. It affirms that manual work can carry a form of knowledge that engages intelligence, and even a way of thinking about the world. This claim is not insignificant. It prepares the ground for what would later be called the Royal Art: not an art reserved for kings, but an art that refuses to be reduced to execution without spirit.

The Old Charges: bringing the craft into the realm of knowledge

When the Liberal Arts appear in the background of the Old Charges, this is neither a genuine scholastic inheritance nor an academic reminiscence. The liberal arts in Freemasonry take on a very different function here. They serve to shift the craft, to bring it—firmly, yet without clamour—into the order of recognised knowledge. The Old Charges do not describe what operative masons were from a sociological point of view; they state what they refused to be.

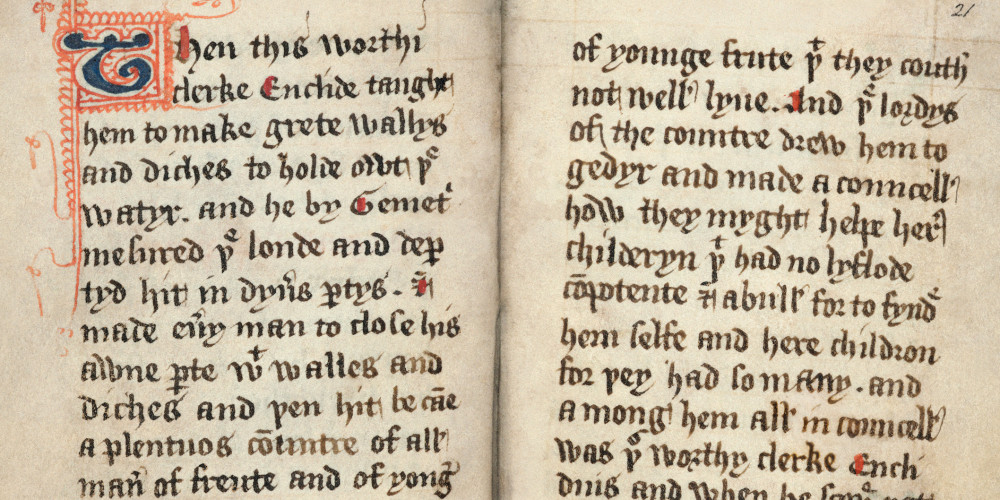

Pages from the Cooke Manuscript, one of the earliest Old Charges texts, dating from the early fifteenth century, presenting the legendary history and foundations of the mason’s craft.

These texts, written between the late fourteenth century and the eighteenth century, have often been read as naïve documents, mixing professional regulations, biblical legends, and improbable genealogies. Such a reading misses the essential point. The Old Charges do not seek historical plausibility. They construct legitimacy. They respond to a simple yet formidable question: how can a manual craft present itself as the bearer of a form of knowledge that goes beyond execution?

The answer is always the same, and it is insistent: through Geometry. Masonry is assimilated to one of the Arts of the Quadrivium, that is, to a discipline concerned with number, order, and proportion. This choice is far from incidental. Geometry is not merely a tool for building; in medieval thought, it is a key for reading the world. It orders space, grounds harmony, and makes visible a rationality that exceeds immediate use.

By claiming Geometry, the Old Charges remove Masonry from the category of mechanical arts. They do not deny the craft; they transfigure it. The building site is no longer merely a place of production; it becomes a place of knowledge. The mason is no longer only the one who executes, but the one who understands what he brings into being. The liberal arts in Freemasonry appear here as a discreet yet determined strategy to refuse assignment to intellectual inferiority.

This strategy is extended through the figures invoked by the Old Charges. References to David, Solomon, Charles Martel, or Athelstan are not intended to establish a credible historical lineage. They situate Masonry within a symbolic space where knowledge, power, and construction are linked. If kings honoured masons—or were masons themselves—then the craft cannot be reduced to a merely servile activity. It participates in a higher order.

It is here, implicitly, that what would later be called the Royal Art begins to take shape. Not as a flattering title added after the fact, but as the logical consequence of an ancient claim. To say that Masonry belongs to the Liberal Arts is to affirm that it touches upon what orders both the world and the human being. The Old Charges do not theorise this idea. They state it, repeat it, and almost impose it, as an evident truth to be defended against a social order that would otherwise continue to relegate masons to the rank of mere executants.

The liberal arts in Freemasonry therefore do not originate in the rituals of the nineteenth century. They find a more explicit formulation there, but their function is already present in these early texts: to make the craft a place of thought, and gesture a path of access to knowledge.

From the Fellowcraft to the Liberal Arts: moving from gesture to discernment

When the liberal arts appear explicitly in the rituals of Freemasonry during the nineteenth century, this is not in order to transmit encyclopaedic knowledge nor to provide the Fellowcraft with a scholastic education. Their function lies elsewhere. They intervene at a precise moment in the initiatic path, at the point where the Mason is no longer only the one who learns to do correctly, but the one who begins to question what he does and why he does it in this way.

The degree of Fellowcraft marks a shift. The Entered Apprentice receives, imitates, repeats. He learns through the body, through the eye, through habit. The Fellowcraft, by contrast, is set in motion. He travels. He circulates. It is no longer simply a matter of acquiring a technique, but of connecting what he sees, what he measures, and what he understands. The Liberal Arts are situated precisely in this in-between space: they are neither abstract nor immediately operative. They form the gaze.

The Trivium and the Quadrivium are not presented as disciplines to be mastered, but as organising principles. The Trivium refers to right speech, to the capacity to name, to reason, to transmit without confusion. It entails a new responsibility: that of thinking what one says and saying what one thinks. The Fellowcraft is no longer sheltered by the silence of the Entered Apprentice. He enters into a form of speech that binds.

The Quadrivium, for its part, shifts the centre of gravity even further. Arithmetic, Geometry, Music, and Astronomy are not invoked for their technical content, but for what they suggest: a world that is structured, measurable, ordered, yet never reducible to immediate utility. Geometry, in particular, does not refer merely to tracing or proportion. It becomes a way of thinking space, relationship, and right place.

The liberal arts in Freemasonry thus accompany an inner transformation. They are not intended to produce a scholar, but to form a man capable of discernment. The Fellowcraft learns that gesture is never neutral, that it engages a vision of the world, a particular way of inhabiting space and time. It is no accident that these Arts appear within the journeys: they require leaving a fixed point behind, accepting movement, and even discomfort.

It is here that an essential difference with simple technical transmission comes into play. The craft teaches how to do. The Liberal Arts teach how to understand what one does. Between the two there is no opposition, but an inner hierarchy. Gesture comes first, but it is not sufficient. Without this elevation of perspective, work risks closing in on itself, becoming repetition without awareness.

By integrating the Liberal Arts at the heart of the Fellowcraft’s path, Freemasonry does not deny its operative origins. It draws their consequences. It affirms that work on the stone has value only insofar as it is accompanied by work on intelligence and meaning. It is at this level that the liberal arts in Freemasonry cease to be a historical reference and become a lived experience.

From Geometry to the Royal Art: an assumed claim

Geometry occupies a singular place within the whole of the Liberal Arts. It is not one art among others. It is the one through which the craft of building can present itself as something other than a mere technique. The liberal arts in Freemasonry converge toward it as toward a point of crystallisation. It is no accident that the Old Charges establish it as a founding principle, nor that speculative rituals grant it such central importance.

Geometry does not merely measure. It orders. It relates. It introduces intelligibility where there would otherwise be nothing but an assembly of materials. In this sense, it already serves as a mediation between gesture and thought. The geometric line is not simply a line drawn: it is a decision, a choice, an orientation. It presupposes a gaze that anticipates, that projects, that understands the whole before the part.

It is from this perspective that the expression Royal Art can be understood. It surprises, and at times it irritates. It can seem excessive, pretentious, even anachronistic. Yet it does not designate an art reserved for the powerful, nor a symbolic ornament added after the fact. It expresses a precise claim: that of an art which refuses to be confined to execution, because it touches the very order of the world.

Thirteenth-century miniature attributed to Matthew Paris, from the Cotton Nero D. I manuscript, depicting Offa, son of King Warmund of the East Angles, giving instructions to the master of the works during the construction of Saint Albans Abbey. The master holds a compass and a square, instruments of medieval geometry.

To say that Masonry is a Royal Art is to affirm that the work it undertakes concerns not only utility, but right measure. The term “royal” refers less to political power than to the idea of inner sovereignty. What is royal is that which does not depend on immediate use, that which escapes the sole logic of production, that which demands a responsibility proportionate to what is brought into being.

The liberal arts in Freemasonry here find their point of fulfilment. They are not an accumulation of knowledge, but a preparation. A preparation for a gaze capable of discerning order behind matter, form behind gesture, meaning behind the work. Without this preparation, the Royal Art would be reduced to an empty formula. With it, it becomes an exigence.

This exigence is not comfortable. It compels one to refuse simplifications, to avoid settling for decorative symbolism or abstract morality. It commits the Mason to asking what he is truly building, and according to which inner proportions. The Royal Art is not an additional degree; it is a way of holding together what history had separated: hand and mind, craft and knowledge, act and thought.

Perhaps this is where the true audacity of Freemasonry lies. In claiming the Liberal Arts and in calling itself the Royal Art, it does not seek to elevate itself artificially. It simply refuses to consent to a mutilated vision of human work. And it recalls, without emphasis, that to build always means more than to build.

Conclusion – Liberal Arts and the Royal Art

That Freemasonry has preserved its reference to the Liberal Arts is far from incidental. It could have abandoned it without difficulty, as it has sometimes done. If it did not, this is probably not out of loyalty to an old classification, but because this reference expresses something essential about the work it undertakes. The liberal arts in Freemasonry remind us that gesture does not suffice on its own, and that construction is never purely technical. The Royal Art signifies nothing other than this requirement: refusing to reduce the craft to mere execution.

By Ion Rajolescu, Editor-in-Chief of Nos Colonnes — serving a Masonic voice that is just, rigorous, and alive

Discover our selection of lodge working tools, many of which are derived from the instruments of geometry.

1 What are the liberal arts in Freemasonry ?

The liberal arts in Freemasonry refer to a symbolic framework inherited from the Trivium and Quadrivium, expressing the Companion’s passage from manual work to understanding.

2 Why do the liberal arts mainly appear at the Fellowcraft degree?

Because the Fellowcraft degree marks a shift from execution to discernment, and the liberal arts accompany this movement toward reflective understanding.

3 Are the liberal arts merely a medieval legacy?

No. Their use in Freemasonry is not about reviving an old curriculum, but about asserting a particular conception of knowledge and dignity.

4 What is the difference between liberal arts and servile arts?

Liberal arts concern the formation of the mind, while servile arts historically referred to manual trades long regarded as intellectually inferior.

5 Why does Geometry hold a central place in Freemasonry?

Because it unites action and understanding, and historically allowed Masonry to claim its place within the realm of legitimate knowledge.

6 What are the Old Charges?

The Old Charges are foundational texts of English operative Masonry, combining professional regulations, legendary narratives, and symbolic claims about the craft.

7 Do the Old Charges describe the real social status of medieval masons?

No. They primarily express a symbolic and intellectual claim rather than a sociological description.

8 Why is Freemasonry called the Royal Art?

The Royal Art expresses the refusal to reduce the craft to mere execution, affirming its connection to knowledge and meaning.

9 Are the liberal arts still relevant today?

Yes, because they continue to question the relationship between technique, knowledge, and responsibility.

10 Are the liberal arts replaced by sciences in some rites?

Yes, some rites have modernized the terminology, but the underlying symbolic issue remains unchanged.

Read the full transcript of the podcast here for those who prefer reading or want more detail.

Podcast – Liberal Arts and the Royal Art

The Liberal Arts appear explicitly in Masonic rituals during the nineteenth century, at the moment when the Fellowcraft’s path is structured as a passage from gesture to discernment. This late appearance raises questions. It can seem surprising. It may even feel like a reference to an old, academic, almost outdated classification, to the point that some rites have chosen to replace it with the more contemporary language of the sciences. Yet this substitution is not neutral. The liberal arts in Freemasonry are not an erudite survival. They express something fundamental about how Freemasonry understands knowledge, work, and the dignity of the craft.

The Liberal Arts did not originate in Freemasonry. They form the foundation of intellectual education in Latin Antiquity, later taken up and systematised during the Middle Ages. Their purpose was not to train technicians, but to shape men capable of thinking, speaking accurately, measuring, ordering, and contemplating. They are divided into two groups: the Trivium and the Quadrivium. This division is not arbitrary. It corresponds to two ways of approaching reality: through language and through number.

The Trivium comprises Grammar, Dialectic, and Rhetoric. It forms the mind through the word. It teaches how to name things correctly, to reason without confusion, and to transmit thought without distortion. The Quadrivium brings together Arithmetic, Music, Geometry, and Astronomy. It introduces an ordered world governed by proportion and relation, beyond immediate utility. Together, these arts led to philosophy and theology, regarded as the highest forms of knowledge.

This knowledge was called liberal because it was meant to free the individual from immediate necessity. By contrast, the so-called servile or mechanical arts referred to manual and technical trades. This opposition is decisive. It is not merely pedagogical, but anthropological. It establishes a hierarchy of forms of work. It separates what belongs to the mind from what belongs to the hand, and it durably relegates the building trades to a subordinate position, despite their central role in shaping medieval Europe.

It is here that Freemasonry enters into tension with this classification. Emerging precisely from the building trades, it nevertheless lays claim to the Liberal Arts. This choice is not accidental. It is not based on a historical misunderstanding. It is a claim. The liberal arts in Freemasonry are not intended to describe the social reality of operative masons. They express what these craftsmen refused to be: mere executors deprived of intellectual dignity.

The Old Charges help to clarify this shift. These texts, written between the late fourteenth century and the eighteenth century, combine professional regulations, legendary narratives, and symbolic affirmations. They do not aim at historical precision. They construct legitimacy. And that legitimacy rests on a decisive assimilation: Masonry is presented as belonging to Geometry.

This choice is fundamental. Geometry is not merely a measuring tool. In medieval thought, it is a key for reading the world. It orders space, reveals proportion, and establishes relationships. By identifying itself with Geometry, Masonry leaves the realm of mechanical arts and enters that of the Liberal Arts. It affirms that the act of building involves an understanding of order, not merely the capacity to execute.

This claim is reinforced by the figures invoked in the Old Charges: David, Solomon, Charles Martel, Athelstan. Their historical accuracy is secondary. What matters is the symbolic space they create. Masonry situates itself where power, knowledge, and construction are not separated. It asserts that the craft may belong to a higher order than mere production.

It is in this context that the expression Royal Art takes on its meaning. It does not designate an art reserved for kings, nor an honorary title. It expresses a requirement: the refusal to reduce the craft to simple execution.

When the Liberal Arts reappear explicitly in rituals during the nineteenth century, they naturally take their place in the Fellowcraft’s journey. This degree marks a shift. The Entered Apprentice learns through imitation and the body. The Fellowcraft, by contrast, is set in motion. He travels. He connects. The Liberal Arts are not presented as a curriculum to master, but as a framework for reading. They shape perception. They introduce discernment.

The liberal arts in Freemasonry thus remind us that gesture is never neutral. It carries a vision of the world. It presupposes an understanding of space, number, and rhythm. Without this elevation of perspective, work closes in on itself and becomes unconscious repetition.

By preserving the reference to the Liberal Arts, Freemasonry affirms that the construction of the Temple is not merely material. It engages intelligence, measure, and right speech. It reminds us that building always means more than building.

I WANT TO RECEIVE NEWS AND EXCLUSIVES!

Keep up to date with new blog posts, news and Nos Colonnes promotions.