The Ankh Cross in Freemasonry: A Symbol of Life, Passage, and Light

The Ankh Cross in Freemasonry evokes an echo rather than a belonging. A symbol that comes from elsewhere, it holds no official place in Masonic ritual, yet it sometimes appears discreetly — in the background of a lodge decoration or within a Rite of Egyptian inspiration. Its presence is marginal, almost incidental, and yet it invites reflection. Why does this ancient sign, born on the banks of the Nile, still resonate within certain initiatory circles? And what does the Ankh Cross in Freemasonry truly express, if not the constant desire to link matter and breath, the visible and the invisible?

Popularised in the twentieth century by counter-culture, the Ankh Cross fascinates both scholars of ancient Egypt and those who seek, through symbols, bridges between traditions. In the loop rising above the Tau, the initiate perceives a universal movement — the tension between the earthly and the spiritual, between the horizontality of the world and the verticality of the principle. It replaces none of the Masonic symbols; rather, it sheds another light upon them — a reflection arriving from a different horizon.

- 1. What is the origin of the Ankh Cross in Freemasonry?

- 2. What is the symbolic meaning of the Ankh Cross in Freemasonry?

- 3. How did the Ankh Cross enter Masonic tradition?

- 4. What does the Ankh Cross reveal to Freemasons today?

- 5. Conclusion – The Ankh Cross in Freemasonry, a living memory of breath

- 6. FAQ – The Ankh Cross in Freemasonry

- 7. Podcast— The Ankh Cross in Freemasonry

What is the origin of the Ankh Cross in Freemasonry?

Long before it appeared in the lodge decorations of the so-called Egyptian Rites, the Ankh Cross had already belonged for millennia to the sacred heritage of ancient Egypt. Also known as the Ansate Cross or Cross of Life, it can be seen on countless reliefs, held in the hands of the gods or presented to the Pharaoh as a divine gift.

The word Ankh — or Anokh — means “life” or “I am” in ancient Egyptian. It may be compared with the Hebrew Anokhi, meaning “I”, a rare form of the personal pronoun. There is no proven linguistic link between the two, but rather a shared resonance: the verb that affirms being, the breath that declares life. The Ankh thus speaks of the inner nature of existence, and perhaps, at its origin, of the very essence of the gods.

Appearing as early as the First Dynasty, around thirty-one centuries before our era, the Ankh symbolises the divine power transmitted to humankind. It is often shown being held to the mouth of the dead to impart the eternal breath, or held by Isis or Osiris like a key opening the gates of eternity. Its shape — a Tau cross surmounted by a loop — expresses a double movement: the earthly and the celestial, the corporeal and the spiritual.

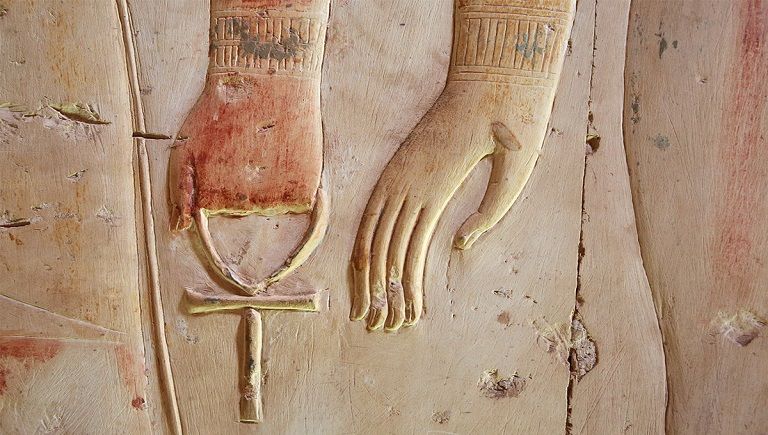

Amon offering the Ankh Cross to the pharaoh — symbol of life bestowed by the divine

Within Freemasonry, the Ankh never became an official emblem. It circulated instead through the hermetic and oriental currents of the eighteenth century, carried notably by Cagliostro, before being adopted in the following century by Egyptian-inspired systems such as Misraim and, later, Memphis. From then on, the Ankh Cross in Freemasonry came to be seen not as a ritual sign but as a symbol of affinity — a discreet bridge between the wisdom of ancient Egypt and the spirit of Enlightenment Freemasonry.

What is the symbolic meaning of the Ankh Cross in Freemasonry?

Like all crosses, the Ankh Cross reveals a duality — the contrast between above and below, heaven and earth, matter and spirit. Yet its unique shape gives it a very distinct character. Instead of being the simple intersection of a horizontal and a vertical line, it takes the form of a Tau surmounted by an oval loop.

The vertical shaft may be seen as the image of material existence, the life of action and embodiment. The arms of the cross mark a boundary, suggesting the limits of physical life. The loop that rises above them opens towards another state of being, another level of consciousness — a passage beyond. Some have interpreted this as a representation of reincarnation, the curve of the loop symbolising the cycle of deaths and rebirths. It is an interesting idea, though without historical foundation, for there is no clear evidence that the ancient Egyptians held such a belief.

More broadly, the Ankh can be read as a figure of Earth and Heaven, echoing the Masonic symbolism of the Square and Compasses. The Tau — shaped like a double square — may represent the material world, marked by the number Four, while the almost circular loop recalls the Compasses, emblem of the heavens, marked by the number One.

Others see in the Ankh the union of masculine and feminine principles, of activity and receptivity: the Tau as a symbol of creative force, and the loop as the image of the womb. This reading accords well with the myths of ancient Egypt, where every male god had a divine consort, and together they gave birth to a son — forming a sacred triad such as Osiris, Isis and Horus, or Ptah, Sekhmet and Nefertum.

As with all great symbols, each person finds within the Ankh a reflection that speaks to them. That is its power — to open a space of many meanings, a creative movement through which one may come to know oneself more deeply.

How did the Ankh Cross enter Masonic tradition?

The history of the Ankh Cross in Freemasonry does not begin within the temples of speculative Masonry, but in the learned rediscoveries of the eighteenth century. When Europe fell under the spell of ancient Egypt, scholars and initiates saw in its hieroglyphs the reflection of a primordial wisdom. The Ankh, often described by travellers as the “cross of life”, quickly captivated hermetic and Rosicrucian circles: in a single sign, it seemed to gather together the ideas of life, light, and spiritual passage.

Within Freemasonry, the symbol appeared only at the margins, carried by these oriental influences. The so-called Egyptian Rites — first Misraim and later Memphis — adopted it within their decorative framework, not as a ritual emblem but as an ornament of continuity. The Ankh there evoked regeneration, the transmission of breath, and life prevailing over death.

Johann August von Starck (1741-1816), founder of the Clerics of the Temple, a Masonic system inspired by the Knights Templar and Rosicrucianism

More surprisingly, the Ankh Cross had already appeared in 1766 within another system of higher degrees: the Clerks of the Temple, founded by Johann August von Starck, a Protestant minister and German scholar. Drawing inspiration from both Rosicrucianism and Templar tradition, the system claimed to perpetuate the priestly branch of the Order of the Temple. At the Convent of Kohlo in 1772, the Clerks of the Temple were united with the Strict Observance. In its two highest degrees — Novice and Canon — the altar was adorned with an Ansate Cross, which also appeared on the Order’s official documents. It was interpreted as the union of masculine and feminine principles, following a theological and naturalist reading close to that of the hermetic tradition.

Thus, long before it entered the Egyptian Rites of Freemasonry, the Ankh Cross had already found its place within the symbolic universe of eighteenth-century initiates. It did not belong to Masonic ritual in the strict sense, but to a parallel language — that of a shared search for spiritual life through the symbols of Nature and the Word.

What does the Ankh Cross reveal to Freemasons today?

Though the Ankh Cross appears in no official Masonic ritual, it remains deeply evocative for those who seek the living principle at the heart of their work. Its strength lies not in the authority of any obedience, but in the inner resonance it awakens. In the loop that rises above the Tau, the initiate recognises the passage from form to light, from matter to spirit. It is the very movement of Masonic labour itself: to raise the human being without denying the earth, to unite shadow and radiance within a single breath.

The Ankh Cross therefore speaks of continuity. It tells us that life is never closed, that death itself is only a change of state. In this, it joins the symbolism of the Acacia, the Phoenix, and the Radiant Delta — all signs of regeneration that depend not on time but on awareness. Its message echoes that of the Lost Word: true life does not come to an end; it recognises itself.

At a time when Freemasonry seeks to renew the spiritual dimension of its work, the Ankh may serve as a mirror. It reminds us that the inner temple is not a monument of stone, but a living organism, animated by the same breath that once moved the gods of Egypt and the builders of cathedrals. That breath, Freemasonry calls Light. Egypt called it Life. The meaning is one and the same.

Conclusion – The Ankh Cross in Freemasonry, a living memory of breath

The Ankh Cross in Freemasonry belongs neither to doctrine nor to ritual. It stands within that fertile space where the memory of symbols meets the search for spirit. It is not a mark of affiliation, but a sign of remembrance — a reminder that every initiatory work rests upon a life that gives itself, transforms itself, and passes itself on.

In the Ankh, the Tau represents the building of the world — the order of form, the firmness of foundations. The loop above it suggests the breath that animates the whole, that primal respiration which the Ancients called Life, and which Freemasonry calls Light. Between the two, the passage remains open: it is the space of humankind, where consciousness awakens and becomes temple.

Divine hand holding the Ankh Cross — symbol of eternal life in Egyptian art

Even as a marginal emblem, the Ankh Cross in Freemasonry bears witness to a universal dialogue between traditions. It reminds us that initiatory truth is never confined within a single system, but moves, circulates, and translates itself across time. Egypt saw in it Life; Freemasonry recognises in it Work — two languages speaking of the same ascent: that of a being learning to unite earth and heaven.

At a time when spirituality so often fragments, the Ankh endures as a symbol of unity. It teaches quietly that Light is not only to be received but to be allowed to pass through us — like a breath that we do not own, but transmit.

By Ion Rajolescu, Editor-in-Chief of Nos Colonnes — in service of a Masonic voice that is just, rigorous, and alive.

From the Ankh Cross to the Rite of Memphis-Misraim! Discover in the ORUMM Higher Degrees collection the echo of ancient Egyptian symbols: aprons, collars and jewels where tradition meets the language of symbols.

1. Is the Ankh Cross a Masonic symbol?

No. The Ankh Cross is not an official Masonic emblem. It appears only within certain so-called Egyptian Rites, such as Memphis or Misraim, where it serves as a decorative or analogical element rather than a ritual sign.

2. What is the origin of the Ankh Cross in Freemasonry?

Its presence dates back to the hermetic and oriental influences of the eighteenth century. Enlightenment scholars and initiates, fascinated by ancient Egypt, saw in the Ankh a figure of life, transformation and spiritual passage.

3. What did the Ankh mean in ancient Egypt?

In hieroglyphic writing, ankh means “life.” The sign expresses the divine power of breath, transmitted from the gods to humankind. It often appears in the hands of Isis, Osiris or the Pharaoh, like a key opening the gates of eternity.

4. Why is the Ankh Cross mentioned in Freemasonry?

Because certain lodges, particularly those of the Egyptian Rites, adopted it within their decorative framework. It symbolises continuity between the earthly and spiritual realms, echoing the Masonic search for Light.

5. What connection exists between the Ankh Cross and classical Masonic symbols?

By analogy, the Ankh reflects the same dynamic as the Square and Compasses: the first defines and stabilises, the second expands and elevates. Together, they express the creative tension between Earth and Heaven.

6. What does the Tau represent within the Ankh Cross?

The Tau unites the vertical and the horizontal: it supports, connects, and forms a threshold. In Masonic interpretation, it evokes the limit the initiate must learn to cross in order to rise toward the Light.

7. Why is the Ankh seen as a union of masculine and feminine principles?

In the hermetic reading, developed by authors such as Éliphas Lévi and Papus, the Tau represents the active (masculine) principle, while the loop symbolises the receptive (feminine) one. Their union gives birth to life and balance.

8. What place does the Ankh hold in the Rites of Misraim and Memphis?

It appears there as a decorative emblem of regeneration and rebirth, sometimes associated with the Acacia. Its role remains marginal but illustrates the dialogue between ancient wisdom and modern Masonic thought.

9. Is there a link between the Ankh and the Christian Cross?

Formally yes: the Coptic Cross derives from the Ankh, whose loop became a complete circle. Yet their origin and spiritual meaning are distinct; one speaks of divine life, the other of redemption through faith.

10. What can the Ankh Cross mean for Freemasons today?

It can serve as an inner mirror, reminding the Mason that life does not end with matter and that the true work consists in uniting what is divided. The Ankh Cross thus becomes the quiet sign of a breath passing through humankind toward the Light.

Read the full transcript of the episode here for those who prefer reading or want more detail.

Podcast— The Ankh Cross in Freemasonry

The Ankh Cross in Freemasonry evokes an echo rather than a belonging. A symbol that comes from elsewhere, it holds no official place in Masonic ritual, yet it sometimes appears, discreetly, in the decoration of a lodge or within a Rite of Egyptian inspiration. Its presence is marginal, almost incidental, and yet it invites reflection. Why does this ancient sign, born on the banks of the Nile, still resonate within certain initiatic circles? And what does the Ankh Cross in Freemasonry truly tell us, if not the constant desire to link matter and breath, the visible and the invisible?

Popularised in the twentieth century by counter-culture, the Ankh Cross fascinates both lovers of ancient Egypt and those who seek, through symbols, bridges between traditions. In the loop that rises above the Tau, the initiate perceives a universal movement: the tension between earthly and spiritual life, between the horizontality of the world and the verticality of the principle. It replaces none of the Masonic symbols — it simply casts another light upon them, like a reflection arriving from another horizon.

Before appearing in the décor of lodges working under the so-called Egyptian Rites, the Ankh Cross had already belonged for millennia to the sacred heritage of ancient Egypt. Also known as the Ansate Cross or Cross of Life, it can be seen on countless reliefs, held in the hands of the gods or presented to the Pharaoh as a divine gift.

The word Ankh — or Anokh — means “life” or “I am” in ancient Egyptian and may be compared with the Hebrew Anokhi, “I”, a rare form of the personal pronoun. There is no proven historical or linguistic link between the two, but rather an affinity of meaning — the verb that affirms being, the breath that declares life. The Ankh thus speaks of the inner nature of existence and, perhaps at its origin, of the very essence of the gods.

Appearing as early as the First Dynasty, around thirty-one centuries before our era, the Ankh symbolises the divine power transmitted to humankind. It is often shown being held to the mouth of the deceased to impart the eternal breath; elsewhere it adorns the hands of Isis or Osiris, like a key opening the beyond. Its form — a Tau surmounted by a loop — expresses a double valence: earthly and celestial, corporeal and spiritual.

Within the Masonic context, this sign never became an official emblem; it moved through the hermetic and oriental currents of the eighteenth century, carried notably by Cagliostro, before being adopted in the following century by systems of Egyptian inspiration such as Misraïm and, later, Memphis. From that point on, the Ankh Cross in Freemasonry was understood less as a ritual sign than as a symbol of affinity, a discreet bridge between the wisdom of ancient Egypt and the spirit of Enlightenment Freemasonry.

The Ankh Cross in Freemasonry is not an official symbol, but its distinctive form invites meditation. It consists of a Tau surmounted by a loop. The Tau combines a planted vertical — the axis, the elevation — with a grounded horizontal — the limit, the world. It may be seen as a threshold: a post and a lintel, a simple structure that serves as a doorway — what supports, what defines, and what invites passage. Above it, the loop introduces the curve of breath, the opening that transcends the boundary and connects the human to the principle.

Thus understood, the Ankh becomes a figure of passage — a threshold between two planes of reality, the incarnate and the transfigured life. By analogy, it recalls the tension that unites the Square and the Compasses: the one fixes and defines, the other opens and elevates. The Ankh expresses that same movement of the soul that opens above the world, not abandoning it but integrating it.

In the hermetic tradition, as expressed by Éliphas Lévi and Papus, the Ankh represents the union of masculine and feminine principles, active and receptive, whose balance gives rise to life. Oswald Wirth saw in it the breathing of the world — inspiration descending from above, expiration returning to the earth: two movements of a single breath.

This double reading is not an official interpretation within Freemasonry, yet it illuminates a spiritual function: reminding the initiate that the work consists in holding together the axis and the limit, the doorway and the passage. In this sense, the Ankh Cross in Freemasonry may be read as a metaphor for inner work — uniting what seems opposed, transforming the limit into an opening, letting life circulate between the visible and the invisible.

The history of the Ankh Cross in Freemasonry does not begin within the temples of speculative Masonry, but in the learned rediscoveries of the eighteenth century. When Europe became fascinated by ancient Egypt, scholars and initiates saw in its hieroglyphs the echo of a primordial wisdom. The Ankh, described by travellers as a “cross of life”, soon captivated hermetic and Rosicrucian circles: in a single sign, it gathered together life, light, and passage.

Within Freemasonry, this symbol first appeared at the margins, carried along by these oriental influences. The so-called Egyptian Rites — Misraïm, then Memphis — adopted it within their decorative system, not as a ritual emblem but as an ornament of continuity. The Ankh there recalled regeneration, the transmission of breath, and life triumphing over death.

More surprisingly, the Ankh had already appeared in 1766 within another system of the Higher Degrees: the Clerks of the Temple, founded by Johann August von Starck, a Protestant minister and German scholar. Inspired by Rosicrucianism and Templar tradition, this system claimed to perpetuate the priestly branch of the Order of the Temple. At the Convent of Kohlo in 1772, the Clerks of the Temple were united with the Strict Observance. In its two highest degrees — Novice and Canon — the altar bore an Ansate Cross, which also appeared on the Order’s official documents. It was interpreted as the union of masculine and feminine principles, following a theological and naturalistic reading close to that of hermetic thought.

Thus, long before it entered the Egyptian Rites of Freemasonry, the Ankh had already found its place in the symbolic universe of eighteenth-century initiates. It did not belong to Masonic liturgy as such, but to a parallel language — that of a shared search for spiritual life through the symbols of Nature and the Word.

Though the Ankh Cross appears in no official ritual, it remains evocative for those who seek the living principle. Its power lies not in the authority of any obedience, but in the inner resonance it awakens. In the loop that rises above the Tau, the initiate recognises the passage from form to light, from matter to spirit. It is the very movement of Masonic labour itself: to raise the human without denying the earth, to unite shadow and radiance within a single breath.

The Ankh speaks of continuity. It says that life is never closed, that death itself is only a change of state. In this, it joins the symbolism of the Acacia, the Phoenix, and the Radiant Delta — signs of regeneration that depend not on time but on consciousness. Its message echoes that of the Lost Word: true life does not end; it recognises itself.

At a time when Freemasonry seeks to renew the spiritual dimension of its work, the Ankh may serve as a mirror. It reminds us that the inner temple is not a monument of stone, but a living organism, animated by the same breath that once moved the gods of Egypt and the builders of cathedrals. That breath, Freemasonry calls Light. Egypt called it Life. The meaning is the same.

The Ankh Cross in Freemasonry belongs neither to doctrine nor to ritual. It stands within that fertile space where the memory of symbols meets the search for spirit. It is not a mark of affiliation, but a sign of remembrance — a reminder that every initiatic work rests upon a life that gives itself, transforms itself, and passes itself on.

In the Tau, we find the construction of the world, the order of forms and the firmness of foundations. The loop above it suggests the breath that animates all things — that primal respiration which the Ancients called Life, and which Freemasonry calls Light. Between the two, the passage remains open: it is the space of humankind, where consciousness awakens and becomes temple.

Even as a marginal emblem, the Ankh Cross in Freemasonry bears witness to a universal dialogue between traditions. It reminds us that initiatic truth is never confined within a single system, but moves, circulates, and translates itself through time. Egypt saw in it Life; Freemasonry recognises in it Work — two languages speaking of the same ascent: that of a being learning to unite earth and heaven.

At a time when spirituality tends to fragment, the Ankh remains a symbol of unity. It teaches quietly that Light is not only to be received, but to be allowed to pass through us — like a breath that we do not possess, but transmit.

I WANT TO RECEIVE NEWS AND EXCLUSIVES!

Keep up to date with new blog posts, news and Nos Colonnes promotions.