Rose Cross: Origins, Transformations, and the Quiet influence of a Foundational Myth

The Rose Cross occupies a singular place in the history of ideas. Born from a meticulously crafted fiction, it evolved into one of the most enduring myths of Western modernity. Its fascination lies in the way it weaves together utopia, spiritual rebellion, and a longing for total knowledge at a time when Europe was searching for new ways to reconcile Faith and Reason. Beneath the surface mystery, the Rose Cross reflects the effort of an entire generation of thinkers to articulate a vision of human experience that was more coherent, more exacting, and genuinely enlightened.

- 1. What is the Rose Cross, and why does this myth still fascinate?

- 2. The Rosicrucian Manifestos: what do the texts of 1614–1616 actually say?

- 3. The Tübingen Circle: how did a theological environment turn a fiction into a programme of reform?

- 4. From myth to use: how did Rosicrucianism arise?

- 5. Rose Cross and Freemasonry: is there really a connection?

- 6. The Rose Croix Degree: a faithful heir or an unrelated creation?

- 7. The Rosicrucian Revival in the 19th and 20th Centuries: Fragmentation, Reinventions, and Ruptures

- 8. Conclusion: the Rose Cross, a Symbol Reinvented in Every Century

- 9. Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

- 10. Rose Cross: Origins, Transformations, and Misunderstandings Around a Myth

What is the Rose Cross, and why does this myth still fascinate?

The Rose Cross appeared in seventeenth-century Europe as a discreet proposition built on the belief that knowledge, faith, and the inner quest could still speak to one another despite the fractures of the age. The texts that introduce it do not form a coherent system; instead, they outline the silhouette of a learned fraternity committed to intellectual and spiritual renewal, without ever defining its structure.

It is precisely this indeterminacy that ensured its lasting influence. The Rose Cross creates a space in which the central tensions of the era — religious authority, scientific curiosity, and the search for a truly operative light — can be understood from a different angle.

The Rosicrucian Manifestos: what do the texts of 1614–1616 actually say?

The three Rosicrucian Manifestos — the Fama Fraternitatis (1614), the Confessio Fraternitatis (1615), and the Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreuz (1616) — form the foundational matrix of the myth. They present themselves as the disclosure of a learned fraternity committed to a work of intellectual and spiritual renewal.

Yet nothing in these texts confirms the existence of an organized order. What the reader encounters instead is a literary construction that blends religious reform, philosophical speculation, and humanist aspiration, all conveyed in the idiom of the Early Baroque. Far from laying out a program, the Manifestos act as a signal — giving shape to the notion that a new relationship to knowledge and faith might be emerging at the threshold of modernity.

Who was Christian Rosenkreuz, and why is this figure a literary creation?

In the Manifestos, Christian Rosenkreuz is introduced as the founder of a learned brotherhood established in the fifteenth century. His story follows the familiar pattern of early modern initiation narratives: a young nobleman fallen on hard times, he is said to have travelled through the East, encountered scholars, gathered spiritual and scientific knowledge, and later founded a discreet community charged with preserving this inheritance.

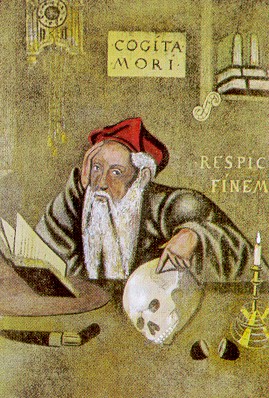

Allegorical portrait of Christian Rosenkreuz, the fictional figure of the seventeenth-century Rosicrucian Manifestos. Anonymous representation from the later iconographic tradition.

His very name reveals his literary nature. Christian Rosenkreuz — the “Rose” and the “Cross” fused into a single surname — has no historical grounding. It functions as a compact emblem, capable of carrying the entire symbolic programme the authors sought to suggest. The name does not point to a real person; it announces a project.

Nothing in the narrative allows us to identify Rosenkreuz with a historical figure. The biographical elements — formative wandering, encounters with Eastern doctrines, the transmission of a reserved knowledge — clearly belong to a crafted literary motif.

Rosenkreuz thus stands as a vehicle for an ideal, a character designed to embody the possibility of intellectual and spiritual renewal in a Europe still fractured by religious conflict. He operates less as an individual than as a symbol: that of an enlightened knowledge conceived as a remedy for the impasses of contemporary thought.

Did the “Fraternity of the Rose Cross” really exist?

The Manifestos portray the Fraternity of the Rose Cross as a community founded in the fifteenth century by Christian Rosenkreuz — structured, disciplined, and in possession of scientific, medical, philosophical, and spiritual knowledge that it now wished to offer to the world. Taken at face value, one might be tempted to imagine a fully constituted initiatory order that had quietly survived the centuries, hidden from view.

Yet no source prior to the 1610s mentions such a fraternity, and no document confirms the existence of any organization matching this description. Already in their own time, several observers suspected that the Fraternity was a construct rather than the belated disclosure of a secret institution.

Later historical research confirmed this intuition. The origins of the Manifestos can be traced to a specific environment: a small group of Lutheran theologians and students later referred to as the Tübingen Circle. Around Johann Valentin Andreae (1586–1654), future pastor and acknowledged author of the Chymical Wedding, gathered minds shaped by the Lutheran piety of Johannes Arndt (1545–1621), the great utopias of Thomas More (1478–1535) and Tommaso Campanella (1568–1639), the medical and philosophical speculations derived from Paracelsus (1493–1541), and a fashionable hermetic vocabulary.

When Andreae later described the Fraternity as a ludibrium — a “game” or “playful fiction” — this was not a gratuitous hoax but a deliberate literary device. The Fraternity of the Rose Cross functions as a crafted fiction aimed at critiquing a Lutheran orthodoxy perceived as too dry while proposing, through narrative, a different way of relating faith, reason, and knowledge of the world.

What did not exist was an organized fraternity of the kind depicted in the Manifestos. What did exist was a clearly identifiable intellectual milieu, animated by a desire for spiritual reform and by the conviction that a broader, more luminous knowledge could help guide Christian society in their time.

Why did the Manifestos disrupt intellectual Europe?

The publication of the Manifestos between 1614 and 1616 came at a particularly delicate moment. Early seventeenth-century Europe was strained by intensifying religious tensions, a flood of polemical writings, and the rise of new scholarly practices that had not yet found stable institutional forms. In such a volatile landscape, the promise of a learned fraternity — free from confessional quarrels and able to unite theology, natural philosophy, and a renewed approach to medicine — had an immediate and powerful resonance.

Part of the shock came from the tone of revelation adopted by the texts. They appeared to unveil an active community, said to have been at work since the fifteenth century and now ready to offer its light to a fragmented Europe. For many readers, this promise addressed the growing sense that traditional religious authorities were hardening just as the emerging sciences still struggled for recognition.

The Manifestos also stood at a crossroads of intellectual influences. They carried Paracelsian overtones deeply rooted in Protestant Germany, drew on hermetic language familiar to humanist circles, and echoed reformist impulses close to early Pietism. This unexpected blend created the illusion of a broader and more structured intellectual movement than the small circle that actually produced the texts.

The reaction was swift. Supportive pamphlets, hostile attacks, vehement critiques, and enthusiastic endorsements circulated widely. The fact that René Descartes (1596–1650) considered such a fraternity plausible — enough to travel to Germany in hopes of meeting its members — speaks volumes about their impact.

The Manifestos unsettled Europe not because they revealed a secret society, but because they gave literary shape to aspirations already alive in the culture: the longing for a unified knowledge, distrust of rigid orthodoxies, and the search for an inner reform capable of reconciling faith with an emerging understanding of the world. Their influence stems from this convergence, rather than from any hidden lineage preserved across centuries.

The Tübingen Circle: how did a theological environment turn a fiction into a programme of reform?

The Tübingen Circle is not merely the milieu from which the Manifestos emerged; it also clarifies their intent. In the early seventeenth century, this group of theologians reflected on what they saw as the spiritual exhaustion of official Protestantism and the inability of confessional controversies to sustain a genuine inner life. The Rosicrucian writings address this concern: through a fictional framework, they suggest that another way of seeking truth might be possible — less dogmatic, and more attentive to the moral, scientific, and social demands of their time.

The Circle is also marked by a distinctive attitude toward knowledge. Rather than rejecting the innovations of emerging science or the legacy of hermetic thought, its members attempted to integrate these currents into a living theology. The Rose Cross thus becomes an imaginary laboratory, a space where intellectual and spiritual convergences — impossible within the institutional realities of the day — could be explored.

Finally, the Tübingen milieu introduced a decisive gesture: it demonstrated that fiction could serve as a critical tool. The Rosicrucian Fraternity, far from being offered as a model to imitate, functions as a mirror held up to churches and scholars alike, inviting them to measure the distance between their ideals and their practices.

Why is the original Rose Cross fundamentally Lutheran?

The Lutheran imprint of the Manifestos is not a peripheral detail: it shapes their entire approach to reform. Their authors belonged to a milieu formed by the heritage of the Reformation and by the internal tensions of early seventeenth-century Lutheranism, torn between strict orthodoxy and a more inward form of piety. Within this context, the figure of the Rosicrucian Fraternity reactivates several distinctly Lutheran themes: the centrality of individual conscience, a distrust of institutional excesses, and the conviction that a living faith must be continually renewed.

One also finds the influence of Johannes Arndt (1545–1621), whose practical piety — rooted in a theology of the inner life — proved decisive for a generation of pastors seeking to move beyond sterile doctrinal disputes. The Manifestos extend this sensibility: they imply that genuine reform cannot be imposed from above, but arises from the transformation of the individual, guided by knowledge ordered toward the good.

Finally, the original Rose Cross proposes no sacramental mediation, no clergy, no hierarchical structure — markers that confirm its Protestant matrix. It speaks directly to the conscience, as an invitation to discern what might be enlightened, corrected, or renewed in a world where the Churches sometimes seemed to have lost sight of their own vocation.

What roles were played by Arndt, Andreae, Paracelsus, and Pansophia?

Several intellectual currents converge in the Manifestos, each shaping a particular dimension of the original Rose Cross. The interiorised piety of Johannes Arndt (1545–1621) provides a spiritual framework in which reform is no longer merely institutional but ethical and personal. His influence is visible in the Manifestos’ insistence on inner transformation, moral life, and individual responsibility.

Johann Valentin Andreae (1586–1654), often identified as one of the chief architects of the project, contributes the literary form: a taste for allegory, a narrative structure, and the critical use of fiction. For him, storytelling is never entertainment; it is a tool for thinking differently.

Johann Valentin Andreae (1586–1654), Lutheran theologian and acknowledged author of the Chymical Wedding. Long considered one of the minds behind the Rosicrucian Manifestos, he later described the Fraternity as a ludibrium, emphasizing its deliberately literary and critical nature.

The presence of Paracelsus (1493–1541) does not point to material alchemy but to his vision of the world: a nature understood as intelligible, dynamic, and woven with correspondences. This outlook oriented the authors toward a broader understanding of medicine, natural philosophy, and their connections with theology.

Finally, Pansophia plays a decisive role. More than a taste for encyclopaedism, it expresses the humanist ambition to unify theology, philosophy, natural sciences, history, and ethics into a coherent whole. Figures such as Johann Heinrich Alsted (1588–1638) systematised this aspiration to total knowledge; others, like Jakob Böhme (1575–1624), gave it a more mystical colouring. The Manifestos reflect this drive toward unified knowledge — a vision in which true understanding transcends disciplinary boundaries and remains oriented toward spiritual life and the common good.

Does the Rose + Cross symbol really mean what people think it means?

The symbol of the Rose Cross has often been interpreted as a fusion of Christian heritage with a more ancient hermetic tradition. Yet the Manifestos themselves do not support these later readings. Originally, the association of the rose and the cross refers above all to a Lutheran Protestant imaginary, deeply familiar to the authors of the Manifestos.

Martin Luther’s seal (1483–1546), adopted in 1530, features a black cross set upon a white rose: a theological emblem rather than a mystical symbol. For the Reformer, the cross represents Christian faith, and the rose expresses the inner joy that flows from justification by faith. The link made by the Tübingen Circle extends this iconography without adding the alchemical or esoteric meanings that would emerge in the seventeenth and especially the eighteenth century.

The roses appearing in the coat of arms of Jakob Andreae (1528–1590), the grandfather of Johann Valentin Andreae, reinforce this lineage. Here again, the symbol signals allegiance to the Lutheran tradition, not a hermetic cryptogram. The original meaning invites us not to search for a hidden secret, but to read the Rose Cross as a literary metaphor, rooted in Protestant culture, serving a project of spiritual and intellectual reform.

From myth to use: how did Rosicrucianism arise?

Rosicrucianism did not emerge from an unbroken tradition, but from an effect of reception. As soon as the Manifestos appeared, readers across the German-speaking lands, England, and the Netherlands interpreted them as evidence of a real order, custodian of knowledge inaccessible to ordinary people. This reading — contrary to the original intention of the Tübingen Circle — generated a series of successive appropriations, each selecting from the Manifestos the themes it deemed meaningful.

In the seventeenth century, Rosicrucianism thus became a constellation of practices rather than a coherent system. For some, it took the form of a Paracelsian current focused on renewing medicine and natural philosophy. For others, it became a mystical orientation in which inner faith was reconciled with hermetic speculation. In many cases, readers retained less the ethical and theological message of the Manifestos than their symbolic motifs — sometimes only marginally present in the original texts.

The transition from myth to use therefore stems from a fertile misunderstanding. Conceived as a literary laboratory for thinking about reform, the Rose Cross became a canvas for multiple projections. Each reader saw in it what they wished to find — alchemy, ancient wisdom, a renewal of reason, or a hidden tradition — to the point that Rosicrucianism came to designate a shifting doctrinal landscape rather than a unified doctrine.

Why did the Rose Cross so quickly become synonymous with alchemy?

The association between the Rose Cross and alchemy does not stem from the doctrine of the Manifestos, but from their reception. Admittedly, The Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreuz (1616) borrows the vocabulary and motifs of alchemy—operations, metals, fusion, purification. Yet this apparatus is a literary device, fully in keeping with the baroque taste for allegorical narratives, not the expression of operative practice. The Manifestos value “alchemy” in a spiritual sense—inner transformation, discernment, moral reform—far more than any work performed in a laboratory.

The shift toward material alchemy came later. In the German-speaking world, authors already engaged in hermetic sciences, such as Michael Maier (1568–1622), read the Manifestos through their own conceptual frameworks. Maier instinctively projected onto Christian Rosenkreuz the alchemical patterns that permeate all his work, integrating the Rose Cross into a hermetic–alchemical tradition it did not originally claim.

Illustration from Atalanta Fugiens (1617) by Michael Maier (1568–1622), one of the major works of Baroque alchemy. Seventeenth-century readers frequently projected this imagery onto the Rose Cross, helping to create the later — and historically unfounded — association between the Rosicrucian Manifestos and operative alchemy.

This appropriation soon reached England, where scholars such as Robert Fludd (1574–1637)—deeply shaped by hermeticism—welcomed the Manifestos as the imagined confirmation of a cosmological wisdom already developed in their writings. For such thinkers, the Rose Cross had to be alchemical, because their own systems were.

Gradually, the learned public retained above all the imagery: emblems, allegories, symbols of transformation. The Rose Cross became a symbolic reservoir accessible to hermeticists, Paracelsian physicians, and lovers of allegoria. This interpretive shift came to dominate the seventeenth and especially the eighteenth century, to the point of obscuring the fact that the Manifestos sought above all to propose an ethical, theological, and intellectual reflection on the state of Christendom. By the eighteenth century, the shift was so complete that the terms “Rose Cross” and “alchemist” became almost interchangeable, both in scholarly literature and in the popular imagination.

The first “Rosicrucians”: pietists, physicians, hermetic–alchemical circles?

The first readers who identified themselves as “Rosicrucians” did not form a homogeneous group. The seventeenth century saw the emergence of a mosaic of profiles drawn to the Manifestos, each finding in them an echo of their own spiritual or intellectual concerns.

One category consisted of pietists — in the broad sense, meaning Protestants devoted to the inner life, personal devotion, and moral reform. For them, the Fraternity symbolised less a secret order than a revitalised Christian ideal, freed from dogmatic polemics.

Others came from Paracelsian circles: physicians and natural philosophers convinced that nature possessed an intelligible structure. They perceived in the Rose Cross a symbolic language consistent with their vision of a medicine grounded in “signatures” and the correspondences woven into the created world.

Added to these were authors from hermetic–alchemical circles, in which hermetism, symbolic cosmology, and spiritual alchemy formed an often inseparable whole. They read the Chymical Wedding as the echo of an ancient sapiential tradition, even though Andreae’s intentions were primarily literary.

Finally, alchemists — scarcely distinguishable from the hermeticists of their time — saw in the Chymical Wedding an illustrated confirmation of their own operative imagination. This interpretation contributed to progressively fixing the equation Rose Cross = alchemy, which would become almost self-evident by the eighteenth century.

This early “Rosicrucianism” was therefore not a structured movement, but a zone of resonance in which different spiritual, medical, and symbolic sensibilities recognised in the Manifestos a mirror of their own expectations.

Rose Cross and Freemasonry: is there really a connection?

The question of the relationship between the Rose Cross and Freemasonry has long occupied Masonic historiography. Yet it rests on a late amalgam. The Rosicrucian Manifestos appeared between 1614 and 1616; speculative Freemasonry only truly emerged somewhat later, in seventeenth-century England and Scotland. No institutional, doctrinal, or organisational link connects the two phenomena at their origin.

This does not mean that one exerted no influence on the other. Both movements developed within neighbouring intellectual milieus: Protestant scholars, readers receptive to the new sciences, admirers of symbolism, Paracelsian physicians, and members of a cultivated elite familiar with European scholarly networks. The cultural climate was shared, but their structures and aims differed.

Seventeenth-century Scottish and English lodges contain no explicit reference to the Rose Cross in their rituals. The earliest hint of an association appears in Muses Threnodie (1638) by the Scottish poet Henry Adamson, declaring: “For we be brethren of the Rosie Crosse; We have the Mason Word, and second sight.” This testimony proves nothing, except that certain cultivated circles in Edinburgh were already linking Rosicrucian and Masonic imaginaries—out of curiosity rather than established tradition.

Portrait of Elias Ashmole (1617–1692), antiquarian, scholar, and enthusiast of alchemy, initiated as a Freemason in 1646. Often — and wrongly — presented as a bridge between the Rose Cross and Freemasonry, he represents instead a sociological overlap: a milieu in which hermeticists, Paracelsian physicians, and learned men interacted without belonging to the same initiatic tradition.

Likewise, scholarly figures such as Elias Ashmole (1617–1692), antiquarian, historian, enthusiast of alchemy, and initiated Freemason in 1646, illustrate a sociological overlap: supposed Rosicrucians, hermeticists, physicians, and Freemasons sometimes moved in the same circles, without one movement arising from the other.

It was only in the eighteenth century, particularly in Germany, that certain initiatory systems sought to fuse the Rose Cross and Freemasonry explicitly — but this was a late construction, often far removed from the original meaning of the Manifestos. This phenomenon belongs to a later phase of Masonic history: the era of the high degrees.

Through which channels did Rosicrucian imagery indirectly reach Masonic circles?

The influence of Rosicrucianism on Freemasonry did not pass through the lodges themselves, but through intermediate milieus where ideas, books, and scholarly speculations circulated. Three main vectors played a decisive role in the seventeenth century.

The first was that of Protestant scholarly networks, highly structured across the German-speaking lands, the Netherlands, and Britain. Professors, pastors, physicians, and antiquarians exchanged manuscripts, treatises, and commentaries. The Manifestos were quickly integrated into these circuits, not as foundational texts of an order, but as intellectual curiosities discussed among many others.

The second channel consisted of the emerging learned societies — or their informal predecessors: circles of antiquarians, natural history groups, study circles. Here again, the Rose Cross was not a model but a literary enigma, stimulating reflection on the relationship between science, religion, and symbolism.

The third vector was the printed book, whose rapid expansion accelerated the diffusion of the Manifestos and their commentaries. What struck readers was not doctrinal content but the imaginative force of the Fraternity: a learned, discreet group, morally exemplary and oriented toward the common good — a motif that would later find an echo, more than a century afterward, in certain forms of Masonic sociability.

Thus, Rosicrucian influence was less a matter of direct transmission than of cultural transfer: a set of symbolic codes, narratives, and expectations circulating through cultivated milieus before eventually reaching, much later, certain Masonic spheres.

Why do the earliest Masonic rituals contain no Rosicrucian elements?

A close examination of the earliest Masonic sources immediately reveals the absence of any Rosicrucian reference. The oldest texts — the Old Charges, composed between the late fourteenth century and the eighteenth century — present a strictly corporate, Christian, and moral universe. The earliest Scottish ritual catechisms (such as the Edinburgh Register House manuscript of 1696) and their English counterparts (including Sloane MS 3329, c. 1700; Dumfries No. 4, c. 1710; and the Graham Manuscript, 1726) all display the same horizon: professional obligations, rules of obedience, and the biblical narrative of the construction of the Temple.

None of these documents mentions the Rose Cross, nor do they contain the slightest hermetic, alchemical, or pansophic colouring. Their symbolism remains simple: signs, words, scriptural references, and a communal framework primarily oriented toward the discipline of the craft.

The so-called “accepted” lodges, which admitted non-operatives — jurists, ministers, local notables, or scholars — did not transform the lodge into a hermetic circle or learned society. They developed neither pansophic utopias nor projects comparable to the Rosicrucian Manifestos. What does emerge in these milieus are the earliest signs of specifically Masonic esotericism: knowledge transmitted through words, signs, and biblical allusions, serving chiefly as a marker of identity and continuity.

The testimony of Robert Kirk (1691), comparing the transmission of the Mason Word — identified with the names of the pillars Jakin and Boaz — to certain rabbinic usages, shows that symbolic reflection was beginning to take shape. Yet this remained an internal, limited, and scriptural speculation, unrelated to the hermetic–alchemical constructions later associated with the Rose Cross.

The legend of Hiram, which emerged in the early eighteenth century (around 1730), marks a narrative turning point, but it remains posterior to the foundational period and bears no relation to Rosicrucian themes. It belongs to a different development: the birth of an internal Masonic symbolism, not the importation of Rosicrucian motifs.

Thus, any attempt to link Rose Cross and Masonry before the mid-eighteenth century must be considered anachronistic. The two traditions do not intersect at their origin: they occupy distinct spaces, rest on different logics, and will only begin to interact later, within the framework of the high degrees.

The Rose Croix Degree: a faithful heir or an unrelated creation?

The emergence of the Knight — or Sovereign Prince — Rose Croix degree in the eighteenth century marks a decisive moment in Masonic history. It is one of the most well-known and most commented degrees, often wrongly presented as the direct heir of the Rosicrucian Manifestos. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The Rose Croix degree appears in France, probably in Lyon around 1760, within a milieu shaped by a strong current of Catholic mysticism flourishing in the Age of Enlightenment. Its theological colouring is unambiguous: it is a Christic degree, centred on the theological virtues, Calvary, the monogram INRI, Emmanuel, and the Last Supper. None of these themes appears in the seventeenth-century Manifestos.

Rose Cross Knight collar jewel, France, 19th century. It features the pelican feeding its young — a central Christic motif in the French higher-degree tradition.

Moreover, several features of the degree reveal a distinctly Catholic inspiration: ritual kneeling, the mention of the archangel Raphael — found in the Book of Tobit, a deuterocanonical text absent from Protestant Bibles — and the quasi-sacramental structure of the final agape. The Protestant tradition would not have incorporated these elements.

The choice of the name “Rose Croix” does not indicate filiation, but rather the appropriation of a prestigious term that had already drifted far from its Lutheran origin and had come to signify a form of mysterious wisdom. The degree borrows no doctrinal element from the Manifestos: it belongs to a specifically Masonic dynamic shaped by the Christian, mystical and erudite sensibilities of eighteenth-century France.

The hypothesis of a Jesuit influence, advanced by Jean-Marie Ragon in the nineteenth century, may be exaggerated; yet it at least points to the fact that this degree arose in a context where Catholic spirituality and the quest for inner experience were prominent. The figure of Jean-Baptiste Willermoz (1730–1824) illustrates this atmosphere particularly well.

In sum, the Rose Croix degree is an autonomous Masonic creation. It adopts a well-known name, but derives nothing from the Rosicrucian Manifestos. It reflects the spiritual universe of eighteenth-century French Freemasonry, where moral Christianity and occasional hermetic allusions combine to form one of the most striking degrees of the period.

In what sense is the Rose Croix degree a “false friend” of the original Rosicrucianism?

The success of the Rose Croix degree in Masonic systems, especially in the nineteenth century, helped create a long-lasting confusion: many assumed that Freemasonry had preserved, transmitted, or even embodied the legacy of the Rosicrucian Manifestos. The mere use of the same name was enough to suggest a continuity that nothing — absolutely nothing — supports historically or doctrinally.

The Rose Cross of the seventeenth century is a Protestant theological fiction, born on the margins of Lutheran Pietism, shaped by allegory, humanist scholarship, and the pansophic dream of reconciling faith, science and philosophy. The Masonic degree, however, rests on an entirely different framework: Christic, moral, centred on the symbolism of sacrifice and redemption, with some hermetic resonances added according to the taste of the time.

The divergences are not only doctrinal; they are structural. The Rosicrucianism of the Manifestos presents itself as an imaginary pedagogy, almost an intellectual programme disguised in narrative form, whereas the Masonic Rose Croix degree belongs to a graded initiatory progression tied to the internal economy of the high degrees. One develops a utopian and critical myth through story-telling; the other proposes a dramatic ritual marked by Christian emotion and the symbolism of passage.

Moreover, the central themes of the Fama, the Confessio or the Chymical Wedding — universal reform, the fictitious nature of the narrative, the critique of dogmatism, pansophy, the pursuit of wisdom through study — are entirely absent from the Masonic degree. The Lyonnais ritual inherits none of these devices, nor their language, nor their aims.

The Rose Croix degree is therefore a “false friend” in the strictest sense: it uses a prestigious signifier while remaining disconnected from its origin. The name functions as a label with strong symbolic resonance, seized by eighteenth-century Masonic authors to express another vision of spiritual fulfilment — one more Catholic, more affective, more liturgical.

The often-proclaimed link survives only through retrospective imagination. The historian must insist that any direct lineage between the Rosicrucian Manifestos and the Masonic Rose Croix degree is a genealogical illusion, born from the prestige of a name sufficiently polysemic to accommodate all manner of projections.

How did Lyon become the laboratory of the Rose Croix degree?

The emergence of the Rose Croix degree in Lyon in the 1760s was no accident. At that time, the capital of the Gauls was a unique spiritual centre where several currents converged with an intensity found nowhere else in France: Catholic devotion, interior mysticism, European illuminism, survivals of Baroque piety, and an exceptionally active Masonic sociability.

Lyon was first and foremost a city of confraternities, devotions, and spiritual retreats. Local Catholicism was not merely institutional: it was permeated with a sacramental imagination, a taste for liturgy, and a natural familiarity with Christic symbolism. In such soil, a ritual like the Rose Croix — marked by the Last Supper, the theological virtues, and the figure of the redeeming Christ — found an immediately receptive environment.

To this must be added another decisive factor: the presence of a very coherent Masonic milieu, solidly structured around charismatic personalities, foremost among them Jean-Baptiste Willermoz (1730–1824). Deeply attracted to the theosophical doctrines of Martinès de Pasqually, he played a major role in shaping the spiritual orientation of the Lyonnais lodges.

In the 1760s and 1770s, all the components of the “Lyonnais style” were already present: explicit Christicity, devotional moralism, attraction to symbols, mystical reading of Scripture, and a desire to raise Freemasonry to an interior plane.

The encounter between this Catholic sensibility and the ceremonial framework of French Masonry produced an atmosphere favourable to the birth of degrees that were more spiritual, more dramatic, more “interior” than those practised elsewhere. The Lyonnais Rose Croix was therefore not the result of any borrowing: it reflected a specific religious and Masonic climate.

Moreover, Lyon was a crossroads: hermetic works circulating from the German-speaking world were read there; the systems of high degrees were discussed; foreign visitors were received. The Rosicrucian imaginary — already largely detached from the original Manifestos — circulated as a totemic word, an emblem of hidden wisdom that each person invested with their own meaning. Such a climate allowed a degree to be called “Rose Croix” without being Rosicrucian.

Thus, Lyon became an initiatory laboratory: a place where Catholic mysticism, an expanding Freemasonry, and the attraction of powerful symbols capable of embodying the ideal of spiritual fulfilment converged. The Rose Croix degree was the direct product of this local alchemy — not of the 17th-century Manifestos.

Why did the Rose Croix degree become the symbolic summit of so many rites?

From the moment it appeared, the Rose Croix degree spread with remarkable speed. Within a few decades, it became the summit—or one of the summits—of several high-degree systems: the French Rite, the Ancient Accepted Scottish Rite, the Rite of Memphis-Misraïm, the Royal Order of Scotland. This success was not the result of any Rosicrucian lineage but of an alchemy that was entirely Masonic.

The first factor is the power of the Christic motif, which gives the degree an emotional intensity that earlier degrees had never reached. The blue degrees establish a moral and symbolic framework; the Rose Croix introduces an existential, almost dramatic dimension. The initiate discovers a more interior horizon, structured by the three theological virtues, the symbolism of the Cross, and the Agape. In an eighteenth-century society still deeply marked by Christianity, this dramaturgy naturally found an immediate resonance.

The second factor is its ritual structure, which clearly sets it apart from the intermediate degrees. Whereas many high degrees multiply narratives and symbolic accumulations, the Rose Croix offers a more concentrated architecture: a simple narrative arc, a word of strong spiritual value, the revelation of a Christic symbol, and a final Agape that seals the whole. This sobriety produces an unusual initiatory effect, almost mystical, which the Masons of the eighteenth century perceived at once.

The third factor is the plasticity of the symbol, which allows the Rose Croix degree to be integrated into very different systems. Catholic in its original form, it can easily become more scriptural, more philosophical, or more symbolic depending on ritual adjustments. It lends itself to reinterpretation without losing its internal coherence. Its name—charged with an aura of mystery—gives it a prestige that far exceeds its historical reality.

Finally, the Rose Croix degree answers a deep expectation: to offer a spiritual synthesis, a point of completion that gives meaning to the entire Masonic journey. After the Hiramic legend, which establishes the symbolism of loss, the Rose Croix offers the opposite movement: that of re-composition, of recovered light, of an inner meaning regained. This dynamic naturally makes it a “summit.”

Thus, the Rose Croix degree became one of the highest degrees because it concentrates, under a prestigious name, the core ambition of all high-degree Masonry: to offer the initiate an image of spiritual fulfilment—not through any fictitious Rosicrucian lineage, but through the internal logic of the Masonic system itself.

The Legend of Ormus: a Late and Groundless Construction?

Among the imaginary genealogies associated with the Rose Cross, none has enjoyed as much success as the legend of Ormus. It appears late, in the 1770s–1780s, within the Gold- und Rosenkreuzer of the “Old System,” founded in Berlin under the influence of Rudolf von Bischoffswerder (1714–1803) and Johann Christoph Wöllner (1732–1800). According to this narrative, the Rose Cross originated with Adam, passed through all ancient traditions, and eventually crystallised in Egypt around a priest named Ormus, converted to Christianity by Saint Mark and founder of the original Order.

This construction has no historical foundation. It belongs to a typically illuminist imagination, nourished by sacred genealogies, mythical chronologies, and a pronounced taste for ancient origins. Nothing in the seventeenth-century Manifestos evokes such a story. Nothing in the earliest forms of Freemasonry suggests even the vaguest trace of a tradition going back to Pharaonic Egypt or to a first-century convert. The legend of Ormus reflects far more the intellectual climate of German Rosicrucian circles in the eighteenth century than any earlier reality.

Its legacy, however, proved considerable. In the nineteenth century, several occultist systems adopted it: the Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia, the Golden Dawn, and later Jacques-Étienne Marconis de Nègre (1795–1868), who introduced the myth into the Rite of Memphis. As it spread, the figure of Ormus became a convenient symbol, providing fictitious antiquity to organisations seeking legitimacy.

The legend of Ormus thus illustrates a recurring mechanism in Rosicrucian history: the creation of retroactive narratives meant to fill a documentary void and offer prestigious genealogies to recent groups. It reflects not a continuous tradition, but an initiatic imagination always ready to reinvent its own past.

The Rosicrucian Revival in the 19th and 20th Centuries: Fragmentation, Reinventions, and Ruptures

The 19th century marks a new stage in Rosicrucian history. After shaping the Baroque imagination of the 17th century and inspiring the para-Masonic systems of the 18th, the Rose Cross becomes one of the central poles of modern occultism. This revival does not extend the original Manifestos; it stems from a profound shift in the spiritual landscape, now marked by Romanticism, individual mysticism, and a reaction against triumphant positivism.

In England, the first modern Rosicrucian structures emerge within the Masonic milieu. The Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia (SRIA), founded around 1865 by Robert Wentworth Little (1840–1878), offers an esoteric Christian teaching organised into nine grades, largely inspired by the German Golden and Rosy Cross. Requiring the Master Mason degree for admission, it becomes a meeting point for symbolic scholarship and mystical aspirations. Several major figures of British occultism are initiated there.

It is in this soil that, in 1888, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn is born, founded by William Wynn Westcott (1848–1925), Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers (1854–1918), and William Robert Woodman (1828–1891). More elaborate and more operative, the system combines ceremonial magic, Hermetic Kabbalah, alchemy, and symbolic psychology. Rosicrucianism serves here not as a historical continuity but as a conceptual framework. The Golden Dawn generates numerous schisms (Stella Matutina, B.O.T.A.) and exerts a lasting influence on Western esotericism throughout the 20th century.

In France, the revival is carried by a milieu where occultism, literature, Catholic esotericism, and Masonic sociability intersect. The Ordre Kabbalistique de la Rose-Croix, founded in 1888 by Stanislas de Guaita (1861–1897) and Joséphin Péladan (1858–1918), brings together Papus (Gérard Encausse, 1865–1916), Oswald Wirth (1860–1943), and other major figures of the time. These circles favour a syncretic approach blending Kabbalah, hermeticism, Christian symbolism, and magic.

Joséphin Péladan, painted by Alexandre Séon around 1892 — a defining icon of the mystical and aesthetic Rosicrucian revival.

Péladan, disagreeing with its Orientalist orientation, leaves the Order to found, in 1890, the Catholic or Aesthetic Rose Croix. Under his direction, the movement acquires a lasting cultural influence: between 1892 and 1897, the Salons de la Rose-Croix in Paris gather painters, sculptors, writers, and composers around a Christian and mystical aesthetic ideal.

Among the artists marked by this singular atmosphere is Erik Satie (1866–1925), whose stripped-down, ironic, and deeply personal universe still bears the discreet but tangible traces of his Rosicrucian experience.

The 20th century sees the emergence of the Rosicrucian organizations most familiar to the general public. The Rosicrucian Fellowship of Max Heindel (1865–1919), founded in 1909, proposes a mystical Christian teaching distributed by correspondence, nourished by astrology and spiritual cosmology. The Ancient and Mystical Order Rosae Crucis (AMORC), founded in 1915 by Harvey Spencer Lewis (1883–1939), develops an international structure combining graded instruction, ceremonies, and a prestigious Egyptianising imaginary. In 1945, the Netherlands see the birth of the Lectorium Rosicrucianum, a gnostic school founded by Jan van Rijckenborgh (1896–1968) and Catharose de Petri (1902–1990), rooted in the original Manifestos but profoundly reshaped.

Across these diverse currents, one conclusion stands out: modern Rosicrucianism is not the direct heir of the 17th-century movement. It retains the name, sometimes certain themes, but diverges from it through its structure, methods, and implicit theology. It no longer maintains any organic link with the Manifestos, and even less with the origins of Freemasonry. What endures, from century to century, is the capacity of the Rose Cross symbol to welcome heterogeneous spiritual aspirations—a mirror in which each era projects its own inner quest.

Conclusion: the Rose Cross, a Symbol Reinvented in Every Century

From the seventeenth century to contemporary organizations, the Rose Cross has never ceased to change its appearance. Born within a very specific context—the German Lutheran pietism of its time, Baroque utopias, and a world of scholarship in which science, faith, and curiosity still converged—it quickly detached itself from its origins to become a vast symbolic receptacle. Alchemists saw in it a mirror of their quest, occultists an authoritative source, para-Masonic fraternities a model of organization, and the schools of the twentieth century a language capable of re-enchanting the modern world.

This plasticity explains its longevity. The Rose Cross survives not because it imposes a doctrine, but because it suggests possibilities: reconciliation, unity, inner transformation. Perhaps this is where its true strength lies—more than in imagined lineages or claimed filiations: in its capacity to cross the centuries without ever being reduced to any single one of them.

By Ion Rajolescu, Editor-in-Chief of Nos Colonnes — serving a Masonic voice that is just, rigorous, and living.

Deepen your journey with our selection of French Rite Higher Degrees.

1. Is the Rose Cross a historically real organisation?

No. The fraternity described in the seventeenth-century Manifestos is a literary fiction created by the theological circle of Tübingen. It never existed as a structured order.

2. What is the precise origin of the name “Rose Cross”?

The name symbolically echoes Martin Luther’s seal (a cross placed on a rose). It does not refer to any medieval lineage, despite later claims.

3. Did Christian Rosenkreuz actually exist?

No. Christian Rosenkreuz is a fictional character, created as a narrative device in the Manifestos. His very name is symbolic wordplay.

4. Did the Rose Cross influence the birth of Freemasonry?

Early Masonic rituals show no link. Some Rosicrucian and Masonic circles merely coexisted in the same scholarly environments in the seventeenth century.

5. Why is the Rose Cross often associated with alchemy?

Because seventeenth- and eighteenth-century alchemists projected their own expectations onto the Manifestos. Rosicrucianism thus became, by extension, a synonym for spiritual alchemy.

6. Is the Masonic degree of Rose Croix genuinely Rosicrucian?

No. It originates in Catholic and mystical contexts and has no doctrinal connection with the Manifestos. The resemblance lies in the name, not in the substance.

7. What role do modern Rosicrucian orders like AMORC play?

They extend the myth within a contemporary spiritual framework through correspondence courses, teachings, and lectures. They do not derive directly from the original Manifestos.

8. Is the Rose Cross a Christian initiatic path?

It was created by Lutherans, but later reinterpretations gave it many faces: Hermeticism, Christian esotericism, occultism, or Gnosticism.

9. Why does the Rose Cross continue to fascinate today?

Because it is not a fixed doctrine. It functions as an open symbol in which individuals can project their own quests: unity, transformation, inner wisdom.

10. Can we speak of a continuous Rosicrucian tradition since the seventeenth century?

No. There have been successive, often contradictory reinterpretations, but no uninterrupted transmission. What endures is the symbol, not the institutions.

Read the full transcript of the episode here for those who prefer reading or want more detail.

Rose Cross: Origins, Transformations, and Misunderstandings Around a Myth

The name is familiar, almost everywhere in the Western imagination: the Rose Cross. A symbol surrounded by fascination, projections, and misunderstandings, claimed by many groups and invoked in countless speculations. But behind this enduring emblem lies a story far more complex, far more fragile, and far more human than what later traditions imagined. This episode offers a clear and sober exploration of the origins of the Rosicrucian Manifestos, their intellectual environment, their reception, and the later constructions—Masonic, occult, spiritual—that took their name long after the original authors had laid down their pen.

The story begins in Germany in the early seventeenth century, with three strange and unsettling publications. The first Manifesto appeared in Kassel in sixteen fourteen: the Fama Fraternitatis. It presented itself as a revelation, announcing the existence of a mysterious “Fraternity of the Rose Cross”, founded two centuries earlier by a certain Christian Rosenkreuz, who had supposedly travelled through the East, gathered hidden wisdom, and returned to Europe to establish an invisible brotherhood devoted to healing, knowledge, and reform. A year later came the Confessio Fraternitatis. Then, in sixteen sixteen, a final and far more enigmatic text: The Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreuz, a curious alchemical novel written in the first person. These writings blended theology, satire, utopian fiction, Paracelsian ideas, and hermetic imagery. They provoked both enthusiasm and hostility across Europe.

Yet the fraternity they described never existed. The most likely author—or at least the principal contributor—was Johann Valentin Andreae, born in fifteen eighty-six, a Lutheran pastor from Württemberg. He later called the Rose Cross a ludibrium: a playful fiction, even a moral provocation. Andreae belonged to the “Tübingen Circle”, a small group of theologians and students who felt that Lutheran orthodoxy had become rigid and spiritually inert. Influenced by Johann Arndt, by Paracelsian thought, and by the utopian visions of More and Campanella, they imagined a renewed Christianity capable of uniting learning, piety, and charity. The Rose Cross was their literary device—half satire, half proposal for reform. Even the name “Christian Rosenkreuz” was symbolic: the rose and the cross appear in the personal seal of Martin Luther, and Andreae’s own family bore arms associating a cross and roses. Nothing in the Manifestos corresponds to the later esoteric constructions attributed to them. The alchemical tone of the Chymical Wedding is a literary convention. The brotherhood never operated, never initiated anyone, never possessed secret sciences. What existed was a small circle of Lutheran thinkers writing fictional works in a Europe shaken by political, religious, and intellectual upheaval.

A myth, however, had been born—and myths follow their own logic. In the decades that followed, the term “Rosicrucian” escaped its original context. Readers across Europe, especially in the German and English-speaking worlds, began interpreting the Manifestos as evidence of a hidden order. Some thinkers, such as Robert Fludd in England, took the texts seriously and attempted to decode their supposed secrets. Others projected alchemy onto them to such an extent that by the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, “Rosicrucian” had become almost synonymous with “alchemist”. The original intention vanished. The fiction became a banner. Hermeticism, alchemy, theology, and early science merged in the Baroque imagination, forming a constellation of themes far removed from Andreae’s intentions.

What about Freemasonry? Could the early lodges have been influenced by Rosicrucianism? Historically, the answer is no. The earliest Masonic documents—the Old Charges from the fourteenth to eighteenth centuries, the Edinburgh Register House Manuscript of sixteen ninety-six, or the Sloane, Dumfries, and Graham manuscripts—contain no trace of Rosicrucian themes. Their world is biblical, moral, and professional. Nothing hermetic, nothing alchemical, nothing utopian. Even the early “accepted” members—lawyers, ministers, scholars—did not transform the lodges into hermetic circles. The symbolic reflection that appeared around the end of the seventeenth century, including the transmission of the Mason Word, remained modest and scriptural. Robert Kirk, writing in sixteen ninety-one, compared the Mason Word to certain rabbinic practices, but nothing in this early symbolic speculation has any connection to the Rose Cross. Freemasonry developed its own symbolic language independently. The Legend of Hiram, which appears around seventeen thirty, marks a turning point, but belongs entirely to Masonic evolution—not to Rosicrucian influence. The meeting between the two traditions occurs later, in the eighteenth century, particularly through the creation of high degrees in France and the German states.

In the German world, alchemical and hermetic circles sometimes adopted Masonic structures and eventually formed groups such as the Golden Rosicrucians, who claimed Templar and Rosicrucian lineage and developed increasingly elaborate genealogies. In France, around seventeen sixty in Lyon, a new degree appeared: the Rose Croix. Today known as the eighteenth degree of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite, it has almost nothing to do with the original Manifestos. Its themes are resolutely Catholic: Faith, Hope, and Charity; the Cross; Emmanuel; and the Last Supper. Elements foreign to Lutheran theology, such as the archangel Raphael, confirm its Catholic origin. The Rose Croix degree is not Rosicrucian. It is a Christian, sacramental, symbolic creation produced within a mystical French milieu, likely connected to circles around Jean-Baptiste Willermoz, long before he structured the Rectified Scottish Rite. The name was borrowed, not inherited.

Outside Freemasonry, the nineteenth century saw the rise of occultism. Romantic spirituality rediscovered the Rosicrucian theme, and new orders emerged: the Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia in eighteen sixty-five; the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in eighteen eighty-eight; and in France, the Kabbalistic Order of the Rose Croix founded by Stanislas de Guaita and Joséphin Péladan. These groups drew inspiration from the Manifestos but followed their own directions, mixing Kabbalah, alchemy, Christian mysticism, and magical practices unconnected to Andreae’s intent. The twentieth century saw further transformations with Max Heindel’s Rosicrucian Fellowship, Spencer Lewis’s A.M.O.R.C., and the Lectorium Rosicrucianum in the Netherlands. Each created its own synthesis—Christian esotericism, occult philosophy, correspondence lessons, or gnostic renewal. None had historical continuity with the seventeenth-century authors, yet all demonstrated the enduring power of the symbol.

The enduring fascination of the Rose Cross does not come from a secret brotherhood that once existed but from the symbolic force of the image itself. A rose and a cross: beauty and suffering, blossoming and structure, the finite and the infinite. A symbol can survive the disappearance of its creators. It can survive even the loss of its original meaning. And that is perhaps why the Rose Cross continues to attract seekers, dreamers, and thinkers. Not because it hides a hidden truth, but because it opens a space where meaning can be sought.

I WANT TO RECEIVE NEWS AND EXCLUSIVES!

Keep up to date with new blog posts, news and Nos Colonnes promotions.