Sun and Moon in Freemasonry: Universal Symbols or Cultural Constructs?

The sun and the moon in Freemasonry occupy such a familiar place in the Lodge that one almost forgets how singular they truly are. Present as soon as the Lodge opens, and associated with the first moments of initiation, they seem to form an obvious language, almost a natural one. And yet, approaching the sun and the moon in Freemasonry already means venturing into a territory where the universal blends with the cultural inheritances that shape the way we interpret symbols. Behind the apparent simplicity of the sun and the moon in Freemasonry lies a more complex story: that of celestial bodies observed everywhere, yet understood through very particular traditions.

- 1. Why did the Sun appear without the Moon in the earliest Masonic rituals?

- 2. When the Moon enters the Lodge: how does it transform Masonic symbolism?

- 3. The Sun–Moon pair: a symbolic system deeply rooted in Europe

- 4. Universal symbolism: what does “universal” really mean in Freemasonry?

- 5. Conclusion: a universal to acknowledge rather than to proclaim

- 6. FAQ – Sun and Moon in Freemasonry

- 7. Podcast – The Sun and the Moon in Freemasonry — Universal Symbols or Cultural Constructs

Why did the Sun appear without the Moon in the earliest Masonic rituals?

In the earliest ritual usages, the Sun appears alone, as if it had never needed a companion. It is already present at the end of the seventeenth century, notably in the Edinburgh Register House Manuscript of 1696, where it serves above all as a moral witness to the oath of the future Mason. Nothing allegorical: a celestial body that illuminates, sees, and judges. This simple and direct role is what defines the early stages of Freemasonry.

When one examines these early manuscripts, one discovers a world still shaped by operative practice: a workshop, rules of the trade, a rhythm governed by daylight. The Sun is enough, because no work is done at night, nor under the Moon. The rituals reflect the life of a craft, not yet an inner search.

The Sun illuminating the city of humankind, illustration from the Splendor Solis, a sixteenth-century German alchemical treatise.

In this context, speaking of the sun and the moon in Freemasonry would not yet have made sense. The symbolic system had not been constructed: there was one useful, structuring celestial body, and nothing more. The Moon would find its place only when the Lodge ceased to be a simple workspace and became a place where the polarities of the self are questioned — a shift in perspective that would profoundly transform the reading of symbols.

When the Moon enters the Lodge: how does it transform Masonic symbolism?

The arrival of the Moon in Masonic rituals is almost discreet… yet it changes everything. One must wait until 1724 and the catechism The Whole Institution of Masonry to see it appear clearly, alongside the Sun, in the list of the twelve Lights. And the contrast is striking: until then, the Lodge lived under a single diurnal star; now it discovers the night, its reflections, and an entire symbolic palette absent from operative manuscripts.

The Graham Manuscript of 1726 takes up this new element and develops it further: the Sun “renders Light day and night,” it says, but the diffusion of that nocturnal light belongs to the Moon — a “dark body off waters,” receptive, linked to the shifting world and to the levels offered by the waters. For a ritual still steeped in Christian symbolism, the association is anything but trivial: the Sun illuminates, the Moon receives, transmits, softens. We are already in an inner, almost psychological dynamic.

From that point on, the sun and the moon in Freemasonry cease to be a backdrop and become a polarity. The ritual begins to play on complementarities: direct light and reflected light, activity and receptivity, expansion and restraint. It marks the entry into a more inward dynamic, where the symbols speak as much to the work of the mind as to the order of the cosmos.

The Moon’s entrance therefore marks a shift. The Lodge is no longer only a workshop lit by day; it becomes a space where one also observes what reveals itself in the fragile glow of symbolic nights. A new reading of initiation begins to take shape.

The Sun–Moon pair: a symbolic system deeply rooted in Europe

This is where the contrast becomes most striking. The sun and the moon in Freemasonry are often presented as a symbolic pair arising from a “natural,” almost spontaneous language: one active, the other receptive; direct light and reflected light; gold and silver.

But as soon as one looks more closely, another reality appears: this distribution of roles is anything but universal. It is deeply rooted in the languages and representations of Europe.In most Indo-European languages, heirs of Latin or Greek, the Sun is masculine and the Moon feminine. And this is precisely the pattern adopted by Masonic rituals, without even noticing it — as if the gender of the celestial bodies were self-evident.

But change the language and everything shifts: in German, the Moon is masculine (der Mond) and the Sun feminine (die Sonne). Irish Gaelic makes both feminine. Hebrew places both in the masculine. And in languages that do not mark gender — Chinese, Thai, Malagasy, for instance — the question does not even arise.

What does this linguistic diversity reveal about Masonic symbolism?

That a symbol never enters a tradition naked. It carries with it an entire cultural backdrop, invisible precisely because it feels self-evident. Freemasonry is no exception: by adopting the Sun/Moon polarities as they appear in European languages, it is in fact universalising a local reading.

This becomes clear in the way the Lodge stages contrasts:

– expansion / reception

– activity / inwardness

– warmth / coolness

– direct light / diffused light

All of this works perfectly… within a culture that has assigned these values to these celestial bodies. Elsewhere, the associations would be different — or even reversed.

Does Freemasonry claim to speak the universal? It first speaks the language that founded it.

This is where a gentle irony emerges: the sun and the moon in Freemasonry seem to embody a timeless cosmic principle, while in reality they reflect above all the way Europe has conceived light, time, and gender. Nothing problematic — as long as one is aware of it.

The danger does not lie in the symbol, but in the illusion that this symbol would mean the same thing everywhere. The good news is that this awareness does not diminish anything: it enriches. It reminds the Mason that what he receives is not a truth fallen from the sky, but a symbolic grammar shaped by a history, by languages, by imaginaries.

And this opens the door to a true intelligence of symbols — one that never confuses the universal with the uniform.

Universal symbolism: what does “universal” really mean in Freemasonry?

The universality of the sun and the moon in Freemasonry stems less from their symbolism than from their objective presence in the sky above all peoples. On that point, Freemasons are not mistaken: everyone sees day follow night, everyone observes the lunar phases and structures time around these phenomena. But believing that this shared experience is enough to produce a universal symbolism is already a confusion, for shared experience never guarantees shared interpretation.

The encounter of the Solar King and the Lunar Queen, illustration from the Splendor Solis, a sixteenth-century German alchemical treatise.

A symbol becomes universal only when it manages to rise above the cultural categories that gave birth to it — and this is almost never the case. The sun and the moon in Freemasonry, as they are understood in European rituals, reveal above all the way our culture — and our language — organises reality. Their supposed universality rests on a common point of departure, but their meaning arises from a framework specific to Europe: a world of strongly gendered, valued, and hierarchised polarities.

Recognising this does not diminish the symbol; it illuminates it differently. The universal lies less in the meaning than in the availability of the celestial body to be interpreted. Everything else — the reading, the polarity, the opposition — always belongs to a tradition. The Mason connects to the universal only by first knowing where his culture begins and where it ends.

What can a symbol truly share across all cultures?

The universality of a symbol never comes from its meaning, but from what in it remains open enough to welcome multiple readings. A phenomenon such as sunrise or the phases of the Moon belongs to this shared zone, for no culture escapes it. Yet the way one describes them, names them, values them, or relates them to one another varies so greatly that it is enough to transform a simple experience into an entire worldview.

A symbol becomes universal only because it remains available, malleable, and capable of being reinterpreted without losing its anchoring in reality. The sun and the moon in Freemasonry rest precisely on this availability, for everyone can recognise their presence in the sky, even if they do not attribute the same qualities to them. This distinction is essential: what we share is the raw material of the symbol, not its interpretive code.

From this nuance, Masonic work can open toward something other than cultural reproduction. The Mason then recognises that the universal does not lie in the values he projects, but in the initial experience — one that may be translated differently according to each tradition.

Why do cultures never read the same things in the same celestial bodies?

A culture never produces a symbol from a celestial body itself, but from the questions it asks, the fears it carries, and the stories it transmits. Two peoples may look at the same sky without seeking the same meaning, for the sky never answers on its own: it answers the expectations of those who question it. The sun and the moon in Freemasonry follow this rule as well, for they reflect first the concerns of Enlightenment-era Europe, not a spontaneous reading of the cosmos.

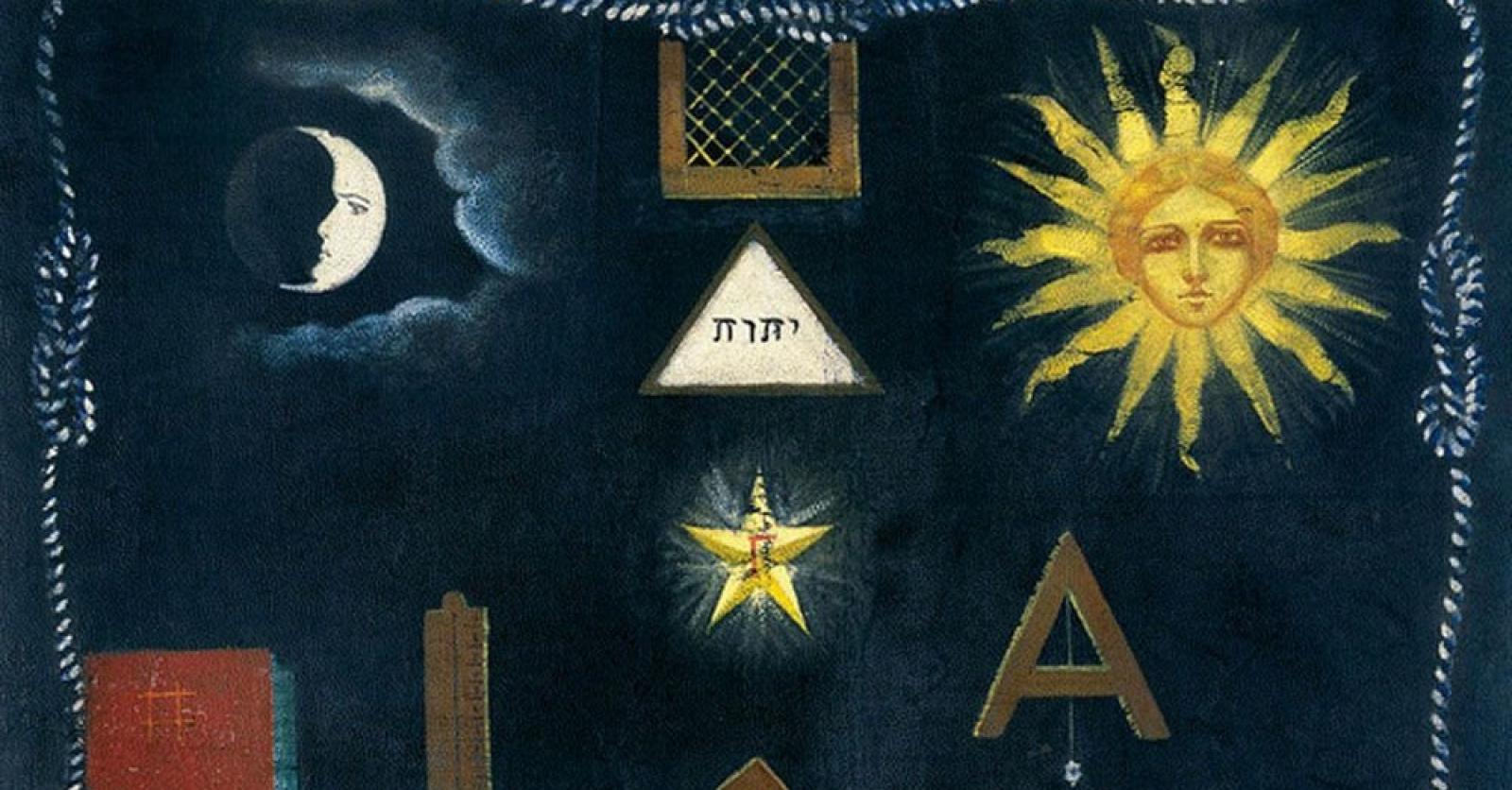

Detail from an old Masonic Tracing Board showing the Sun and the Moon.

Where some traditions see the night as a time of rest or protection, others perceive it as an unstable realm populated by ambiguous forces. In some societies, the Moon is sovereign, giver of order and calendar; in others, it is secondary or even unsettling. What Freemasonry has turned into a harmonious polarity is therefore not a human constant, but a specific cultural choice rooted in a worldview where daylight is supposed to reveal truth.

This gap between identical phenomena and divergent symbolisms does not diminish the Masonic meaning, but it demands greater lucidity. The Lodge does not work with the sky as it is, but with the sky as Europe has interpreted it. Understanding this is recognising that universality does not lie in the symbol itself, but in the possibility each culture has to project into it what carries meaning for her.

What is the real risk in believing in a universal symbolism?

The danger does not lie in the symbol itself, but in the belief that its meaning is self-evident to everyone. The moment we assume that others read the world as we do, we stop questioning the categories that structure our own thinking. The sun and the moon in Freemasonry then cease to be gateways toward the universal and become mirrors in which Europe contemplates itself while imagining it sees all of humanity.

This illusion creates a false common ground: we think we are speaking a shared language, when in reality we are simply speaking more loudly from within our own tradition. Symbolic concordism works in this way, not out of ill will but out of blindness: it equates things that have never been experienced as equivalent. We believe we are drawing cultures closer together, yet we stand above them without realising it.

Symbolic vigilance arises precisely here. It consists in recognising that universality is not something given but something sought — not a symbol imposed, but a patient translation, respectful and aware of its limits. Only under this condition can Freemasonry hope to reach what it calls the universal without confusing it with its own assumptions.

Conclusion: a universal to acknowledge rather than to proclaim

When one follows the path that leads from the early manuscripts to modern practice, one discovers that the sun and the moon in Freemasonry reveal not only a vision of the cosmos, but also the cultural prism through which Europe has conceived order, light, and balance. These celestial bodies, observed by all, acquire meaning only through the categories, stories, and habitual patterns of thought that give them shape. Recognising this situated dimension does not weaken initiatory work; it gives it a more lucid foundation.

A symbol remains alive when it accepts being reread, shifted, or translated through contact with other traditions, without being presented as a self-evident universal. It is by embracing this movement that Freemasonry can articulate what it has inherited and what it seeks to transmit. The Sun and the Moon then retain their depth, not as guarantors of a shared truth, but as markers of a quest that can cross cultural boundaries without denying them.

By Ion Rajolescu, editor-in-chief of Nos Colonnes — in service of a Masonic voice that is just, rigorous, and alive

To go further! The polarities of the Sun and the Moon echo other symbolic systems. You can extend this reflection by reading our article on the Sephirothic Tree.

1. What do the Sun and the Moon represent in Freemasonry?

The sun and the moon in Freemasonry symbolize two complementary modes of light: the direct brilliance of day and the reflected clarity of night. Together, they remind the Mason that the Lodge works with both conscious insight and inner depth.

2. Why does the Sun appear before the Moon in early Masonic rituals?

In seventeenth-century manuscripts, only the Sun is mentioned, because early Freemasonry remained close to operative traditions that worked exclusively in daylight. The Moon appears later, when the symbolic dimension becomes more interior.

3. Why are the Sun and the Moon traditionally associated with active and receptive principles?

This polarity does not come from the sky itself but from European languages, which assign grammatical gender to the celestial bodies and shape their symbolic qualities accordingly. The sun and the moon in Freemasonry inherit this cultural framework.

4. Is the symbolism of the Sun and the Moon universal across all cultures?

No. While the phenomena are universal, their interpretation varies according to languages and traditions. Some languages reverse grammatical genders, and others do not mark gender at all, which directly influences symbolic readings.

5. Why are the Sun and the Moon placed in the East of the Lodge?

They are usually depicted on the eastern wall to signify that Masonic work begins under the sign of light, whether direct or reflected. They symbolically accompany the Apprentice at the fall of the hoodwink.

6. How did European Freemasonry shape the symbolic reading of these two celestial bodies?

It organised them according to cultural oppositions: light/dark, active/receptive, steady/changing. The sun and the moon in Freemasonry therefore reflect a European way of structuring the world rather than a universal symbolic system.

7. When does the Moon first appear in Masonic ritual sources?

The first clear appearance of the Moon is found in the catechism The Whole Institution of Masonry (1724), where it already appears among the twelve Lights of the Lodge. But it is the Graham Manuscript (1726) that offers the first developed symbolic interpretation by associating the Moon with water and nocturnal light.

8. Why does Freemasonry speak of harmony between the Sun and the Moon?

Because they form a symbolic polarity inviting the Mason to work with both the clarity of daytime consciousness and the more interior depth associated with night. This harmony is culturally shaped but serves the initiatory path.

9. How does language influence the meaning of the Sun and the Moon?

In many Indo-European languages, the Sun is masculine and the Moon feminine, which shapes their symbolic roles. Other languages reverse these genders, which radically changes their interpretation.

10. How can universal phenomena be reconciled with culturally specific symbolism?

By recognising that universality lies in the observable phenomenon, not in its meaning. The symbolism of the sun and the moon in Freemasonry is cultural, yet their presence in the sky allows for shared experience and diverse interpretations.

Read the full transcript of the episode here for those who prefer reading or want more detail.

Podcast – The Sun and the Moon in Freemasonry — Universal Symbols or Cultural Constructs

There are, in most Lodges, two silent presences that never utter a word, yet no Mason can ignore them: the Sun and the Moon. They stand in the East, visible as soon as the Lodge opens, like two celestial witnesses placed at the threshold of our gaze. Everyone knows them, everyone has seen them countless times, and yet their presence in the Lodge is anything but obvious. Their symbolism does not reveal itself at a glance. It must be approached the way one approaches an inner light: slowly, carefully, with the humility of someone who knows that a symbol reveals as much as it questions.

In the earliest Masonic manuscripts, the Sun appears alone. We are at the end of the seventeenth century: the Edinburgh Manuscript, dated sixteen hundred ninety-six, mentions the Sun as witness to the oath. The firmament, it says, sees everything, and the Sun illuminates everything. It thus becomes an image of divine justice, the one that brings to light what must be brought to light and reminds each Mason of the gravity of a spoken promise. At that time, Freemasonry remained close to operative practice: one worked in daylight, and the Lodge closed when the Sun went down. It is no surprise that the Sun still dominated the symbolic horizon.

It is only later, at the beginning of the eighteenth century, that the Moon enters the picture. The catechism The Whole Institution of Masonry, dated one thousand seven hundred twenty-four, already mentions it among the twelve Lights of the Lodge. The Graham Manuscript, dated one thousand seven hundred twenty-six, takes up this development and expands it: it describes the Moon as a dark body, proceeding from Water, receiving its light from the Sun. It is called “Queen of the Waters”, and one immediately understands that with it, another dimension opens: an inner, shifting, sometimes uncertain dimension.

From then on, the European Lodge, nourished by inherited symbolic traditions, created a polarity. The Sun came to represent the active, manifest, steady principle. The Moon became the receptive, changing, interior one. Together, they form a kind of symbolic breath: the clarity of day, the depth of night; that which illuminates, and that which reveals differently. And if these oppositions seem self-evident to us today, they do not come from the sky but from our culture. They reflect the way European languages assigned gender to the celestial bodies, shaped their qualities, and built a certain imagination around them.

What we often take for “universal” rarely is. The phenomena are universal: everyone sees the Sun rise, everyone sees the Moon wax and wane. But the interpretation depends on languages, on stories, on traditions. Some languages reverse the genders: in German, the Moon is masculine and the Sun feminine. Other languages do not mark gender at all, which changes the symbolic reading entirely. And this is precisely where the Mason must exercise vigilance: what seems to come from nature often comes from history.

So what remains universal about these two celestial bodies? Their presence, their availability, their ability to be interpreted. Nothing more. Everything else — their meaning, their polarity, their symbolic role — belongs to a particular tradition shaped by European languages, myths, and ways of thinking. Recognising this does not diminish the initiatory work; it makes it more accurate. A symbol truly breathes only when it does not mistake itself for self-evidence.

When we stop projecting onto the universe what our culture has placed there, the Sun and the Moon cease to be certainties. They become invitations. Invitations to reread what we thought we knew. Invitations to recognise what we owe to our language, our history, our way of organising the world. Invitations, finally, to understand that the universal is not something we possess, but something we reach, slowly, by passing through our own limits.

And perhaps this is, ultimately, the Mason’s real work: to hold together what comes from the heavens and what comes from human beings, without confusing the two. Enlightened by the Sun, accompanied by the Moon, he walks in a light that is never simply given, but always constructed — and shared.

I WANT TO RECEIVE NEWS AND EXCLUSIVES!

Keep up to date with new blog posts, news and Nos Colonnes promotions.