Templars and Freemasonry: A Story of Lineage?

The Templars fascinate. Their name evokes chivalry, tragedy, the East, persecution, and, very quickly, the suspicion of buried secrets. Within this rich imaginary, the link between Templars and Freemasonry has imposed itself as an obvious truth for many, to the point of being frequently presented as a historical lineage. But does this apparent evidence withstand scrutiny? Between the documented history of the Order of the Temple and the symbolic constructions of eighteenth-century Freemasonry, the gap is considerable. Should the question therefor be dismissed out of hand? Or should we seek to understand why Templars and Freemasonry ultimately came to meet within the initiatic imagination, at the cost of persistent confusions? It is precisely this shift—from history to myth, and then to symbol—that the relationship between Templars and Freemasonry invites us to examine without complacency.

- 1. Historical origins of the Templars: what does history tell us?

- 2. The fall of the Order of the Temple: a historical end without survivance?

- 3. Templar survivals: what remains after 1312?

- 4. Why did eighteenth-century Freemasonry need the Templars?

- 5. From the Templar myth to Masonic high degrees: a gradual construction

- 6. The Templars as a political and symbolic figure: an acknowledged instrumentalisation

- 7. False history, initiatic truth?

- 8. Conclusion – The Templars: not ancestors, but foundational figures of the Masonic imagination

- 9. FAQ – Templars and Freemasonry: separating myth and history

- 10. Podcast – Are the Templars the ancestors of Freemasons?

Historical origins of the Templars: what does history tell us?

The Order of the Temple emerged in a precise and well-documented context, without any initiatic grey areas. In 1118, in Jerusalem, a small group of knights united to protect pilgrims travelling the roads of the Holy Land. They took religious vows and placed themselves under the authority of the Latin Church. Their official recognition came in 1120 at the Council of Nablus, and then in 1129 at the Council of Troyes, where the Church validated an unprecedented status: that of monk-soldiers.

Representation of members of the Order of the Temple, including knights and a cleric, nineteenth-century illustration.

Installed in a wing of the former royal palace of Jerusalem, believed at the time to stand on the site of the Temple of Solomon, they took the name Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon. Nothing in these origins points to secrecy, hidden transmission, or reserved knowledge. Their Rule, drawn up under the influence of Bernard of Clairvaux, emphasises discipline, obedience, and communal life far more than any esoteric dimension.

The Order’s expansion was rapid. Through donations, a dense network of commanderies established in the West, and their military role in the East, the Templars became a major economic and logistical power in the medieval world. This success, often reread retrospectively as evidence of mysterious knowledge or occult wealth, is in fact explained by an efficient administrative network and by the institutional trust granted by the religious and political authorities of the time.

From a historical standpoint, the Templars were therefore a religious and military order fully embedded in their century. Their spirituality was that of medieval Christianity, their organisation that of an ecclesiastical institution, and their purpose clearly defined. No contemporary source allows them to be seen as the direct or indirect ancestors of a later initiatic structure such as Freemasonry. It is precisely this conclusion, firmly established by history, that will come into tension with narratives developed much later, when Freemasonry sought to inscribe its own story within a more prestigious genealogy.

The fall of the Order of the Temple: a historical end without survivance?

The disappearance of the Templars has nothing to do with mystery or a gradual fading into the shadows of history. It was abrupt, political, and thoroughly documented. After the definitive loss of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1291, the Order of the Temple was deprived of its original purpose. A military power without a theatre of operations, a financial power without a collective project, it became vulnerable in a West where the balance between royal authority, the Church, and institutions was rapidly changing.

In France, this situation intersected with the interests of Philip IV the Fair. The king, engaged in a policy of authoritarian centralisation and facing chronic financial difficulties, was heavily indebted to the Templars. The Order thus appeared both as an inconvenient creditor and as an autonomous institution that was difficult to control. The solution chosen was radical. On 13 October 1307, the Templars were arrested by royal order and accused of heresy, sacrilegious practices, and ritual crimes. These charges, largely standardised in inquisitorial proceedings, rested primarily on confessions extracted under torture.

Pope Clement V, politically weakened and dependent on the king of France, gradually endorsed the process. In 1312, at the Council of Vienne, the Order of the Temple was officially abolished. This decision was not the outcome of a definitive doctrinal judgement, but an act of authority intended to bring an end to a crisis that had become unmanageable. Templar property was transferred to the Hospitallers of Saint John of Jerusalem, and the surviving members of the Order were dispersed, integrated into other religious institutions, or placed under supervision.

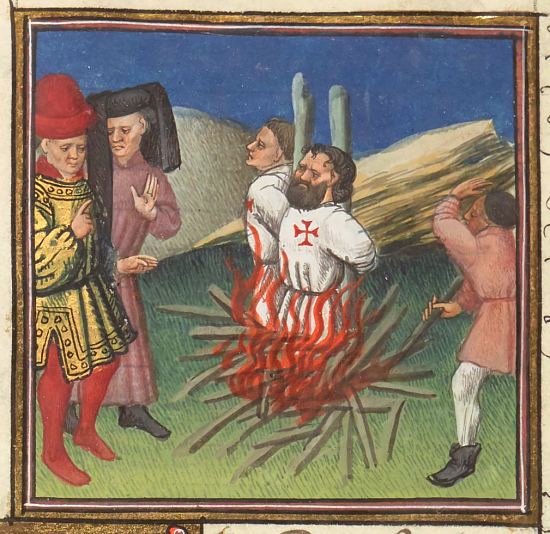

Execution of the Templars, illumination from Laurent de Premierfait’s French translation of Boccaccio’s De casibus virorum illustrium, BnF manuscript no. 229, c. 1440.

The execution of Jacques de Molay in 1314 symbolically marked the end of the Order. From the late Middle Ages onward, it fuelled a tragic memory and a lasting sense of indignation. But this emotional charge must not obscure the essential point: juridically, institutionally, and humanly, the Order of the Temple ceased to exist. There was neither administrative continuity, nor organised transmission, nor clandestine structure that would allow one to speak of survivance in the historical sense of the term.

It is precisely this clear, violent, and—for many—unjust ending that opened a vast space for reinterpretation. Where history records a disappearance, the imagination would long refuse to draw a conclusion.

Templar survivals: what remains after 1312?

The abolition of the Order of the Temple in 1312 was universal. It applied to the whole of Latin Christendom and left no room, either legally or institutionally, for any official continuity. Yet from the late Middle Ages onward, the idea of a Templar survivance began to circulate. This persistence of the theme is not based on established facts, but on specific local situations and on later reconstructions.

In most European kingdoms, the fate of former Templars was relatively prosaic. They were integrated into other religious orders, lived on pensions, or withdrew to houses now placed under the authority of the Hospitallers of Saint John of Jerusalem. No clandestine network, no parallel hierarchy, and no autonomous doctrinal transmission appear in the sources. The disappearance of the Order was therefore real, even if it did not involve the total extermination of its members.

Two exceptions are often invoked. The first concerns the Iberian Peninsula. In Aragon and Portugal, the Templars were replaced by new orders, respectively the Order of Montesa and the Order of Christ. These were political creations, supervised by the papacy, intended to preserve military expertise useful to the Reconquista. These orders inherited property and personnel, but not the Templar identity itself. They were administrative successors, not initiatic survivals.

The second, more famous exception concerns Scotland. The thesis of a flight of the Templars to the north and their participation in the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 rests on late constructions with no documentary foundation. The elements most often cited, such as certain tombstones or Rosslyn Chapel, have been firmly reinterpreted by modern historiography. The chapel dates from the fifteenth century, and the symbols projected onto it belong far more to retrospective readings than to any proven Templar continuity.

One decisive point must be emphasised. This Scottish legend truly appears only in the eighteenth century, and initially within Masonic circles. In other words, it is not medieval history that transmits a Templar survivance to Freemasonry, but modern Freemasonry that projects its own symbolic constructions onto the Templar past. Templar survivance is not a historical fact; it is a late invention, revealing a search for meaning rather than any real continuity.

Why did eighteenth-century Freemasonry need the Templars?

When speculative Freemasonry developed in the eighteenth century, it did so within a very specific social and cultural context. In continental Europe—and even more so in France and Germany—a large proportion of Freemasons belonged to the aristocracy or the upper bourgeoisie. This sociological reality was not neutral. It directly shaped the way the young institution thought of itself, narrated its own origins, and sought legitimacy.

Claiming descent from medieval builders, the anonymous craftsmen of cathedrals, could suit a craft-based masonry. For a Freemasonry that had become speculative, led by nobles, officers, and courtiers, such an origin appeared insufficiently prestigious. A lineage more in keeping with the chivalric and aristocratic ideal of the time was required. The Templars offered an ideal solution: a religious and military order, a fighting elite, embodying discipline, honour, and sacrifice.

To this social dimension was added a political and philosophical reading characteristic of the Age of Enlightenment. The Templars, destroyed by the conjunction of an authoritarian royal power and a compromised papacy, became a convenient figure of persecuted innocence. They could be reread as exemplary victims of religious and monarchical despotism, even as precursors of freedom of conscience. This rereading is obviously anachronistic, but it corresponded perfectly to the intellectual struggles of the eighteenth century.

Finally, the mystery surrounding certain aspects of Templar history played a decisive role. The absence of any documented survivance, far from closing the debate, opened up an immense space for speculation. Where history stops, imagination rushes in. The Templars became the receptacle for every projection: secret doctrine, hidden initiation, a spiritual treasure supposedly brought back from the East. All these elements allowed emerging Freemasonry to endow itself with a dense symbolic past, in the absence of any real historical lineage.

Seal of the Order of the Temple depicting two knights mounted on a single horse.

Thus, the recourse to the Templars did not proceed from an objective transmission, but from an internal necessity. Eighteenth-century Freemasonry did not receive the Templars as an inheritance; it summoned them, reconstructed them, and transformed them into founding figures of a narrative designed to meet its own social, political, and symbolic expectations.

From the Templar myth to Masonic high degrees: a gradual construction

The transition from the historical Templar to the Masonic Templar did not occur all at once, nor in a uniform manner. It unfolded gradually throughout the eighteenth century, in successive layers, through the development of the high degrees. The point of departure is clearly identifiable: the discourse delivered by the Chevalier de Ramsay in 1738. By asserting that Freemasonry descended from the Crusader knights, Ramsay introduced a first decisive shift. He did not yet speak explicitly of the Templars, but he permanently installed the chivalric imagination at the heart of the Masonic narrative.

From the 1740s onward, this imagination spread through a flowering of so-called chivalric degrees, the earliest of which appears to be the Knight of the East, also known as the Knight of the Sword. All of these degrees participate in the same logic: to inscribe Masonic initiation within a heroic and sacred history, situated far upstream from medieval operative masonry. The Templar then becomes an almost inevitable figure. He embodies chivalry, fidelity to a higher cause, and the victim of an unjust power.

In France, this construction reaches a point of balance with the appearance, around the middle of the eighteenth century, of the Sublime Knight Elected, later to become the Knight Kadosh, today the thirtieth degree of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite. This degree synthesises several symbolic layers: the vengeance of Hiram, the denunciation of despotism, and the rehabilitation of an order unjustly destroyed. Here, the Templars appear not as historical ancestors, but as bearers of an imaginary spiritual lineage, intended to lend depth and gravity to the initiatic path.

It is within this framework that the famous legend of a Templar survivance in Scotland crystallises. It allows three elements with no real continuity to be artificially linked: the Temple of Solomon, the Order of the Temple, and modern Freemasonry. This framework, seductive in its apparent coherence, in reality rests on a chain of symbols and narratives rather than on facts. It functions as a founding myth in the strong sense of the term: a narrative that does not describe what was, but what needed to be believed for the symbolic edifice to hold.

The Templar higher degrees therefore do not bear witness to a historical transmission, but to a remarkable ritual creativity. By mobilising the figure of the Templar, eighteenth-century Freemasonry equips itself with a powerful symbolic language, capable of speaking of fidelity, downfall, justice, and transcendence. The Templar myth thus becomes an initiatic tool, not a historical key.

The Templars as a political and symbolic figure: an acknowledged instrumentalisation

From the second half of the eighteenth century onward, the figure of the Templar definitively leaves the terrain of history to enter that of political allegory. This shift is particularly visible in the Germanic and Anglo-Saxon spheres, where certain Masonic systems no longer merely evoke the Templars as moral figures, but claim to work toward their symbolic, or even institutional, restoration.

The Strict Templar Observance, founded around 1754 by Baron von Hund, represents the most fully developed example of this tendency. It asserts the existence of Unknown Superiors, holders of a secret authority derived from the Templars, and explicitly places Freemasonry within a restored chivalric lineage. This carefully staged construction rests on no verifiable historical element. It functions as a device of legitimation, both initiatic and political.

Behind the Templar, however, another figure comes into view: that of the Stuart dynasty, driven from the throne of England in 1688. In certain Jacobite circles, Freemasonry becomes a space of sociability and symbolic diffusion, where the themes of the destroyed Temple, the unjustly overthrown order, and the hope of future restoration take on a barely veiled political resonance. The Templar is no longer merely a medieval martyr; he becomes the mask of a contemporary struggle.

This instrumentalisation reaches its limits at the end of the eighteenth century. At the Convent of Wilhelmsbad in 1782, the Strict Observance officially renounces the claim of a historical Templar lineage, giving rise to the Rectified Scottish Rite. The myth is preserved, but deactivated as a historical pretension. This renunciation marks a decisive turning point: Freemasonry begins to assume that the value of the Templar lies in the symbol, not in the claim to a real inheritance.

False history, initiatic truth?

To affirm that the Templars are not the ancestors of Freemasons does not amount to disqualifying the symbolic constructions associated with them. On the contrary, it restores an essential distinction, too often blurred: the distinction between history, grounded in facts, and initiatic work, which proceeds through symbols, narratives, and exemplary figures. The problem does not arise from the myth itself, but from its confusion with a supposed historical reality.

Within eighteenth-century Freemasonry, the Templar myth functions as a language. It allows central themes of initiation to be expressed: fidelity to a given word, unjust downfall, the passage through ordeal, symbolic death, and the possibility of restoration. In this sense, the Templar is not an ancestor, but a mirror. He offers a figure in which the Freemason may recognise not an origin, but a demand.

Divergences appear when this symbolic language is taken literally. In seeking to prove a historical lineage where there is only a ritual construction, certain contemporary discourses revive old confusions and sustain a fantasised vision of Freemasonry. This insistence on wanting at all costs to “prove” a Templar continuity often betrays a mistrust of the symbol’s own power, as if it needed to be guaranteed by history in order to be acceptable.

Yet the strength of Freemasonry does not lie in the factual veracity of its founding narratives, but in their capacity to structure an inner path. The Templar myth, once stripped of its genealogical pretensions, thus finds its proper place: that of an initiatic tool, demanding and fertile, which has no need to be true in order to be operative.

Conclusion – The Templars: not ancestors, but foundational figures of the Masonic imagination

To the question of whether the Templars were the ancestors of Freemasons, history gives an unambiguous negative answer. No institutional continuity, no organised transmission, and no documented lineage allows a historical link to be established between the Order of the Temple and speculative Freemasonry. To persist in asserting such a link is to deliberately confuse symbolic narrative with the demands of historical scholarship.

Yet to reduce the Templars to a mere Masonic illusion would be a symmetrical error. Their importance lies not in a fictitious genealogy, but in the symbolic power they acquired in the eighteenth century. Freemasonry did not inherit the Templars; it chose them. It turned them into a figure, a language, and a support for meditation on downfall, injustice, fidelity, and the possibility of inner restoration.

In this sense, the Templars occupy a lasting place within the Masonic imagination. Not as claimed ancestors, but as consciously assumed symbols. Provided that history and myth are not confused, this distinction does not impoverish the initiatic approach. On the contrary, it renders it more accurate, more lucid, and ultimately more demanding.

By Ion Rajolescu, Editor-in-Chief of Nos Colonnes — serving a Masonic voice that is just, rigorous, and alive

Beyond the narratives, the symbolic work remains. Discover the regalia and insignia of the vhttps://www.nos-colonnes.com/en/collections/ordre-interieur-regime-ecossais-rectifie-rer.

1 Are the Templars the historical ancestors of Freemasons?

No. No medieval source allows us to establish a historical, institutional, or initiatic lineage between the Order of the Temple and speculative Freemasonry, which emerged in the eighteenth century.

2 Why are Templars so often associated with Freemasonry?

This association developed in the eighteenth century, when European Freemasonry sought prestigious symbolic figures to nourish its imagination, particularly within chivalric high degrees.

3 Did the Templars secretly survive after 1312?

No. The Order of the Temple was juridically and institutionally abolished in 1312. Its former members were dispersed and integrated into other religious structures, without any autonomous continuity.

4 Did the Templars take refuge in Scotland?

This claim has no historical basis. It appears much later, mainly in Masonic circles of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and relies on retrospective interpretations of monuments and symbols.

5 Are Iberian orders such as the Order of Christ survivals of the Templars?

They are administrative successors, created for local political and military reasons. They do not constitute an initiatory or doctrinal survival of the Order of the Temple.

6 Why do Masonic high degrees refer to the Templars?

Because the figure of the Templar allows powerful initiatory themes to be expressed symbolically, such as fidelity, ordeal, injustice endured, and restoration after downfall.

7 Is the Knight Kadosh an authentic Templar degree?

No, in the historical sense. The Knight Kadosh is an eighteenth-century Masonic construction that uses the Templar myth as a symbolic support, not as a real inheritance.

8 Did the Strict Templar Observance truly believe in a Templar lineage?

Yes, at least officially. It asserted the existence of a secret Templar lineage before explicitly renouncing this claim at the Convent of Wilhelmsbad in 1782.

9 Is the Templar myth incompatible with Masonic rigor?

No. The myth becomes problematic only when it is confused with history. Used as a symbol, it can instead enrich initiatory work.

10 What remains of the Templars in contemporary Freemasonry?

A powerful symbolic figure, detached from any genealogical claim, which continues to nourish initiatic reflection on justice, fidelity, and inner responsibility.

Read the full transcript of the podcast here for those who prefer reading or want more detail.

Podcast – Are the Templars the ancestors of Freemasons?

The Templars have fascinated people for centuries. Their name evokes chivalry, the Holy Land, wealth, sudden downfall, and very quickly the idea of a lost or hidden secret. From this fascination emerged a persistent claim: that Freemasonry is the direct heir of the Order of the Temple. To understand what is really at stake behind this idea, one must first return to history, and then clearly distinguish what belongs to established fact from what belongs to symbolic construction.

The Order of the Temple appears at the beginning of the twelfth century, in eleven hundred and eighteen, in Jerusalem. It is a religious and military order, recognised by the Church, whose mission is straightforward: to protect pilgrims in the Holy Land. Its rule, shaped under the influence of Bernard of Clairvaux, governs a life of obedience, discipline, and combat. The Templars are fully embedded in medieval Christendom; their organisation, spirituality, and objectives are known and documented. Nothing in contemporary sources suggests the existence of a secret doctrine or a concealed initiatic transmission.

The end of the Order is just as clearly established. After the definitive loss of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem in twelve hundred and ninety-one, the Templars are deprived of their original purpose. In France, their financial power and institutional autonomy make them vulnerable. In thirteen hundred and seven, Philip the Fair orders their arrest. In thirteen hundred and twelve, Pope Clement the Fifth officially abolishes the Order of the Temple. In thirteen hundred and fourteen, Jacques de Molay is executed. Juridically and institutionally, the Order then ceases to exist. There is no organised continuity, no clandestine structure, no historical survivance.

And yet, the idea of a Templar survivance gradually takes shape. Not in the Middle Ages, but several centuries later. This shift is essential. When speculative Freemasonry develops in the eighteenth century, it brings together men from the aristocracy and the cultivated elites of Europe. This young institution seeks founding narratives capable of giving meaning, depth, and nobility to the initiatic path. It is in this context that the figure of the Templar is invoked.

From the years seventeen hundred and forty onward, Masonic high degrees increasingly integrate a chivalric imagination. The Templar becomes an exemplary figure: faithful to a cause, unjustly struck down, confronted with downfall and ordeal. At first, this is not about claiming an ancestor, but about mobilising a powerful symbol, capable of expressing initiatic truths that ordinary language struggles to convey.

In certain systems, however, this symbolic construction is pushed further. The Strict Templar Observance asserts the existence of a secret historical lineage and claims to work toward the restoration of the Order of the Temple. Behind this staging also appear political stakes, particularly linked to supporters of the Stuart dynasty. The Templar then becomes the mask of a contemporary struggle, and the symbol is burdened with a historical claim it cannot sustain.

This drift reaches its limits at the end of the eighteenth century. At the Convent of Wilhelmsbad, in seventeen hundred and eighty-two, the claim of a historical Templar lineage is officially abandoned. The symbol is preserved, but the confusion is lifted. The value of the Templar is no longer sought in a fictitious genealogy, but in the power of the initiatic language it makes possible.

The conclusion therefore imposes itself with clarity. The Templars are not the ancestors of Freemasons. To confuse myth with history is to confuse two distinct registers. Yet recognising this distinction does not diminish the power of the symbol. On the contrary, it restores it to its proper place. The Templar is not a claimed forebear; it is a chosen figure, an exacting mirror, capable of nourishing initiatic reflection on fidelity, ordeal, and inner responsibility.

I WANT TO RECEIVE NEWS AND EXCLUSIVES!

Keep up to date with new blog posts, news and Nos Colonnes promotions.